I am UAA: Alan Boraas, Professor of Anthropology, Kenai Peninsula College

by Kathleen McCoy |

An anthropology class that he took on a whim during his undergraduate studies led Kenai Peninsula College anthropology professor Alan Boraas on an intriguing path of lifelong discovery.

Then while in line for the photocopier during his last semester at the University of Minnesota, Alan saw an Alaska catalog on the shelf. He flipped it open and saw a beautiful photo of the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus and thought to himself, I'm going to go there and see what happens. He packed all of his belongings and headed up the Alaska Highway. "I crossed over the Alaska border and fell in love," he said. "It was everything I had dreamed of in a place."

Before the trans-Alaska oil pipeline was built, Alan got a job surveying the pipeline corridor for archaeological sites. He left Alaska to finish his master's degree at the University of Toronto, but quickly returned to Alaska in 1972, this time landing in Soldotna.

He worked at a cannery and in carpentry before being approached by Clayton Brockel, a former director of the Kenai Peninsula College, to teach an adult basic education course. Then he talked his way into teaching an introductory anthropology course, where his true passion lies. He took the job, but left briefly in 1979 to complete his doctoral degree at Oregon State University.

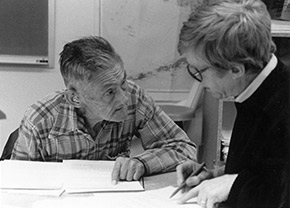

In the mid-'70s, Alan met someone who would forever change his life. He explained

that very little archeological work had been done on the Kenai Peninsula, and he wanted

to excavate a site called Kalifornsky Village. In order to do so, he needed to get

permission from an Alaska Native man named Peter Kalifornsky, the great great grandson

of the man the village was named after. He also spoke with Peter's sister about his

project, and was eventually granted permission to excavate the site.

In the mid-'70s, Alan met someone who would forever change his life. He explained

that very little archeological work had been done on the Kenai Peninsula, and he wanted

to excavate a site called Kalifornsky Village. In order to do so, he needed to get

permission from an Alaska Native man named Peter Kalifornsky, the great great grandson

of the man the village was named after. He also spoke with Peter's sister about his

project, and was eventually granted permission to excavate the site.

Years later, the aging Peter came to Alan for help putting a book of his stories together. At the time, Alan was preparing to embark on another archeological project, but he dropped everything to help Peter with his book. He said, "When a man who is effectively the last speaker of a language asks you for your help, you don't hesitate."

Alan said that Peter would furiously write stories from his childhood, and over the course of four years, the two, with the help of linguist James Kari, carefully edited each story for inclusion in the book. Some of the stories were taboo and not to be shared with the outside community, so Peter was faced with the decision to take those stories to the grave or share them. "There's only one story that I know of that he took to the grave with him," Alan said.

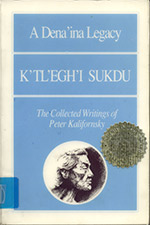

The bilingual book, "Dena'ina Legacy -- K'tl'egh'i Sukdu: The Collected Writings of

Peter Kalifornsky," was published in 1991 and won an American Book Award from the

Before Columbus Foundation in 1992 for its remarkable content.

The bilingual book, "Dena'ina Legacy -- K'tl'egh'i Sukdu: The Collected Writings of

Peter Kalifornsky," was published in 1991 and won an American Book Award from the

Before Columbus Foundation in 1992 for its remarkable content.

Going through this process with Peter inspired Alan to better understand the Dena'ina Athabascan language. He learned a lot about traditional culture, and now works to translate that into what people can understand in today's modern times.

Alan's recent work involves taking Peter's stories and putting them in a form that Dena'ina people, or anyone interested, can use to read and write the language. He uses the Internet to combine audio, video, images and text to help students put together a sentence, click on a button to hear it said and see the grammatical breakdown. "It's considered one of the most complicated languages in the world from a grammatical standpoint," said Alan.

An exchange student from the Netherlands took Alan's course and was able to write a story in Dena'ina by the end of the class. "It confirmed to me that this is going to work," he said.

Alan believes the day will come when the Dena'ina language is taught in every school in Southcentral Alaska, and if not revitalized as an every day language, then revitalized as a ceremonial language. "Our task is to lay the groundwork for this to happen," he said. "It will happen because it's important; it's the language of the place."

An honorary member of the Kenaitze Tribe, Alan was awarded the University of Alaska Foundation Board of Trustees 2009 Edith R. Bullock Prize for Excellence and the Washington Association of Professional Anthropologists 2009 Praxis Award for Excellence in Professional Anthropology for his work preserving Alaska Native language.

Even after 39 years in the field, Alan's work is far from being done. "This work takes forever," he said. "Each thing leads on to the next and the next. I think of it as a process." He said it's not the things that he finds, but the ideas that we can learn from today that are most important. "I've been fortunate to be in a very interesting place at a very interesting time."

"I am UAA: Alan Boraas, Professor of Anthropology, Kenai Peninsula College" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"I am UAA: Alan Boraas, Professor of Anthropology, Kenai Peninsula College" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.