Karen Andrews: 'I never wanted to lead a boring life'

by Kathleen McCoy |

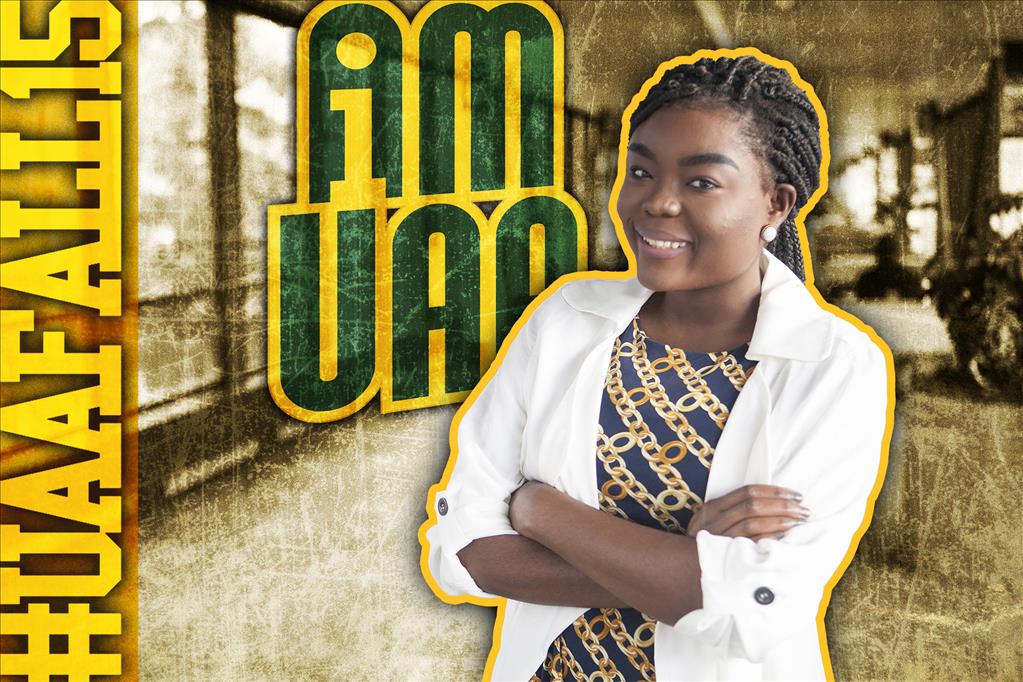

Karen Andrews is the new director of Disability Support Services. (Photo by Philip Hall/University of Alaska Anchorage)

Somehow Karen Andrews knew she was bound for Alaska. She knew it as a kid after reading Jack London's Call of the Wild. She knew it later when she inherited and raised a Malamute puppy named Sitka.

So when the call for applicants to lead UAA's Disability Support Services passed before her, the chance that her Alaska dream might come true tugged.

She was more than a year into her role as associate director for Disability Services at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. She'd led the same office at Stayer University in Virginia before that. Advocating for an even playing field for all college students defined her passion; throw in Alaska and the mix was perfect.

"I had to apply," she says, throwing off a friendly laugh. "I thought, 'They'll never call me... I'm too far away.'"

But they did call. And Alaska's spell was evenly matched by what Andrews found at UAA: a serious commitment to diversity.

For her, disability is diversity. It's the one minority all are eligible for. She reflected on teen skateboarders riding without helmets, or healthy young soldiers who return from war disabled. "Regardless of race, economic status, or cultural background, any one of us can be there in a moment," she says.

As half Native American Indian (of the Delaware and Nanticoke tribes) and half French and African American, she grew up in a family committed to social justice. Perhaps the strongest guidance came from her father, a Frenchman whose mother came from Martinique in the Caribbean.

Her father had one leg shorter than the other. "This was in the '50s, well before the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) and the concept of civil protections. Yet he never let this physical deficit stop him, she said. He played catcher in the Negro baseball leagues and worked as an ocean lifeguard. He was like a fish in water, she said.

"He told me you can do whatever you want, you can be whatever you want, you can go wherever you want-as long as you're willing to work for it," Andrews said.

The family lived by that motto, including sending their brown-skinned girl to a school with no others. "We had segregation, even in Delaware," Andrews recalled. But when it was time for first grade, her parents knew all about Brown versus the Board of Education. They knew she could go to any school they chose.

So they selected an historically all-white school where "I was called the N-word every day for four years," she said. The disgruntled even burned a cross on the family property in protest.

"The good news is I had the family, the love, the support-everything," she said. "I came out of that with no bitterness, no hatred, no nothing. I realized that people were just people. If you're not around somebody different from you, all you know is the stereotype. You don't really know them. That's why I believe so strongly in diversity."

Vision for UAA

"What I saw in the vision and mission statements for UAA was that accessibility is important for all students," she said. "Accessibility and diversity go hand in hand.

"A lot of times people think things like universal design or accessibility are strictly for people that are disabled. But, with multi-modal learning, those design principles are good for all students."

UAA's deep bench of veteran students also attracted her. "This is a category I have a passion for serving," she said.

She also liked the people she met at UAA. "Disability support services cannot function without collaboration," she said. "That's why I believe in reaching out to faculty. Your students are our students and our students are your students."

She said that in the course of her career at three universities, she has sometimes heard complaints: Aren't we discriminating when we allow students to have accommodations? No, Andrews says. "What we are doing is giving them an opportunity. We are not saying this accommodation is going to guarantee you success. We're just going to give you an accommodation that makes it possible for you to succeed."

She explains: "If someone is deaf, that doesn't mean they have a developmental or cognitive disability. It just means they need a sign language interpreter or some other method to be able to communicate."

A major role she plays for UAA is ensuring the school and its services are in compliance with the ADA. But the letter of the law isn't enough; she works hard on the spirit of the law.

"I know the law," Andrews says. "I believe in the law. But I am not going to win people over just citing the law. It is also my role to move the hearts of people."

Andrews describes herself as a "quantitative person living in a qualitative world." She supports a "culture of evidence" to demonstrate the value of her work. "In this era of budget cuts, it is easy to say we don't need this or that department," she said.

"But if you think about the work I do on a daily basis, we talk people off the ledge regularly. We work with students with ADHD. We work with students with PTSD. We invest the time to serve them in a way that the faculty do not, because that is not the role of the faculty. Together we work to make sure the student is successful."

Circuitous path

Although her most recent professional work has been in higher education, Andrews did not start there. She describes herself as a true "child of the '60s." She left home at 18 and never really looked back.

She studied ministry for a time before earning a degree in elementary and special education from Northern Arizona University. She taught for a number of years but also found work in theatre and public television. For a time she worked in Los Angeles as a lighting designer. Another stop came at Ross Perot's Electronic Data Systems, or EDS, where she worked before and during the transition as he sold out to GM.

That led to a career switch: "I thought, 'If I am going to work this hard, I want the work to have eternal value in somebody's life."

Eventually she wound up as an assistant pastor in a congregation along the Rio Colorado in Mexico, where she served more than seven years. Then came a return to education with a master's degree in adult education and development from Strayer University.

Andrew's youngest brother still works and lives in Delaware. Yet Andrews has "worked here and there and everywhere," from Lansing, Mich. to Los Angeles to Virginia to Yuma, Ariz. and many points in between.

"I never wanted to lead a boring life," she says with a grin.

But there's more to it.

"I can't think of one move I made that did not have some purpose compelling me to the next thing. If I had not grown up with a family that hated injustice...if I had not studied education-I would not be here. All of that brought me here today.

"I believe my steps in life are ordered."

Written by Kathleen McCoy, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Karen Andrews: 'I never wanted to lead a boring life'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Karen Andrews: 'I never wanted to lead a boring life'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.