From Mongolia to Alaska: Artist explores engineering at UAA

by Tracy Kalytiak |

Khulan Bazarvaani is a UAA civil engineering student from Mongolia. (Photo by Philip Hall / University of Alaska Anchorage)

Just north of the Mongolia's border with Russia lies a 395-mile-long, mile-deep expanse of water known as Lake Baikal, a place renowned for its situation in a continental rift, its magnificent necklace of taiga pine, larch and cedar and the otherworldly beauty of its cracked and shattered turquoise ice that wind and shifts in temperature create every year.

Khulan Bazarvaani's ancestors once lived there, before the family began migrating to little Buryat villages in Northeast Mongolia. Choibalsan, one of those villages, is where Khulan was born 26 years ago.

"I am Buryat," said Khulan, 26, a UAA civil engineering student, math tutor and granddaughter of herders. "It's a really, really minor ethnic group in Mongolia. Most of the Buryat people still live around Lake Baikal. I'm from eastern Mongolia. My hometown borders to both Russia and China. It's steppeland, flat. I can see the distance there and I miss that."

Khulan Bazarvaani grew up in Mongolia, earned a bachelor's degree in fine arts there and now is pursuing a second bachelor's degree-in civil engineering-at UAA. (Courtesy of Khulan Bazarvaani)

'They're kind'

Khulan was born with a hole in her heart, which created challenges for her as a child.

"I used to faint a lot," she said. "The nice thing about living in a small town is that everybody knows you. They always brought me home or to the hospital."

Nothing could be done in Mongolia to fix her heart problem. Khulan's mother would walk every day to the one computer in the area that had Internet service and comb through information that could help. She lived in Germany for a while when Khulan was tiny, and, after returning home, guided a tour for bird researchers from Germany.

"She talked about me and my heart problem with them," Khulan said. "Then, after the bird researchers returned to Germany, they contacted my mother, helped her and found that amazing opportunity for me to have heart surgery in the German Heart Institute of Berlin."

Khulan's father had worked as a mechanic who certified Russian scales. The advent of electronic scales put him out of work, so his brother gave him a job on his vegetable farm. Khulan's father flew to Germany with his daughter.

"My mother wanted my dad to experience a little bit of foreign life," Khulan said.

Nurses at the German Heart Institute brought her movies but Khulan didn't like the food. "My father had brought dried beef and made garlic soup when I was in the hospital," she said. " 9-11 happened when I was there; everyone was crying in Berlin."

Khulan, then 11, recovered quickly and visited Frankfurt, Nurenberg, Hanover and other places in Germany before journeying back to Mongolia.

Her family moved to Mongolia's capital city, Ulaanbaatar.

"I missed riding horses a lot, I missed looking at the distance," she said. "The nice thing about being a herder-I wasn't a herder but come from herder culture-is, they don't lock the door. They're busy every day, but leave hot tea in a kettle. People get lost; in the countryside there are no streets. Herders expect somebody who's lost will stop by to drink their tea. They're kind."

The path to Alaska

Ulaanbaatar is a city situated in a natural bowl that, in winter, holds the smoke from hundreds of thousands of coal fires.

UAA civil engineering student Khulan Bazarvaani came from a Buryat family steeped in the culture of herding, in Mongolia. (Courtesy of Khulan Bazarvaani)

"The smoke never goes away," Khulan said of the city, which has a population of about 1.3 million people. "The population density is a cause, too. Poor herders follow better hospitals, better education, better employment. They can't afford to buy an apartment immediately so they stay in a yurt and burn coal for heat. Sanitation is a big issue there. No running water, and outhouses where they dig a hole and contaminate the groundwater."

Khulan enrolled at the National University of Mongolia in Ulaanbaatar and earned a degree in fine arts and education.

"My mom is a teacher," Khulan said. "She's an artist. She teaches art to people who are lower-income people: single mamas, unemployed people. She teaches how to use available materials for art, to help people have some income. She's in Inner Mongolia, which is in China. She comes and goes."

Khulan set a goal for herself, to learn English, and decided to find jobs in places that would put her in contact with others who spoke English.

"I started working at guesthouses or museums or wherever I could speak English with tourists because I couldn't afford to go to language courses," she said. "I was working at a guesthouse as a housekeeper and I met a wonderful woman from Alaska who encouraged me and helped me find an internship in Alaska."

That was in 2011. Khulan spent three months working in Seward at the Alaska SeaLife Center.

"That was eye-opening, a culture shock," she said.

Then, two years later, Khulan's friend helped her find another internship with the UAF Cooperative Extension Service's Anchorage office, taking part in research on small-scale mining and air quality being conducted in a joint project of the Extension Service, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium.

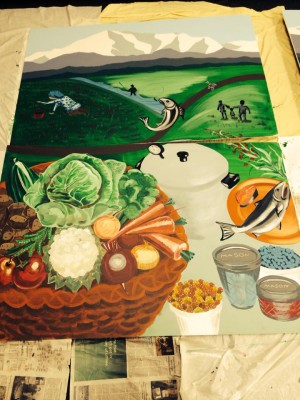

Khulan Bazarvaani, a UAA civil engineering student with a Mongolian bachelor's degree in fine art, created this mural panel depicting a Cooperative Extension Service nutrition program. This and three other panels now hang at the 4-H building on the Alaska State Fairgrounds. (Courtesy of Khulan Bazarvaani)

"I had contact with a lot of people in the environmental field," she said, "So by the time the internship ended, I was really interested in science. I decided to go to school."

Fulfilling dreams

Khulan says it was time-consuming to start working on another bachelor's degree. 'But I thought it was worth it because I want to be someone influential," she said. "What was driving me crazy were people who don't know much about science but they like to fight against things. I think we've got to learn first and then say something or fight. To be an activist, you have to be knowledgeable, right?"

Khulan really wanted to learn about science and how things work.

"That's why I chose civil engineering-not mechanical, not electrical," she said. "Not that I can't learn those things, but civil engineering, it's more toward nature, more toward people. I want to build things which are harmless to nature and people."

Now, Khulan is looking into the specialties within civil engineering and shouldering a heavy load of classes that include statics, physics, data analysis and surveying class and lab.

"I like that," she said. "You know, those orange vests? It's getting warmer outside, so that's fun."

Water resources and structural engineering appeal to her most, at the moment, she said. International students are not permitted to work off campus, for pay, which has narrowed her options for internship opportunities. She hopes, however, to be able to volunteer for Habitat for Humanity.

"I'm new in this field ... still learning, still exploring," she said. "My dream? I'm super excited to be able to build my own house-the design, building my own furniture. And I always talk to my mom. In the far future, we would like to build an education center. That's our dream. I'm pretty grateful I have my life, grateful to have what I have."

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement

"From Mongolia to Alaska: Artist explores engineering at UAA" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"From Mongolia to Alaska: Artist explores engineering at UAA" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.