Research by the bay: a closer look at otters and whales

by Ted Kincaid |

It just figures that the day you dress up for work is the day you're going to get

called to rescue a bewildered sea otter pup making its way toward the Homer Airport.

It just figures that the day you dress up for work is the day you're going to get

called to rescue a bewildered sea otter pup making its way toward the Homer Airport.

Recently, Associate Professor Debbie Boege-Tobin, Ph.D., a marine biologist who teaches at the UAA Kenai Peninsula College's Kachemak Bay Campus (KBC), was busy leading a chemistry lab when she was inundated with phone calls and messages about the wayward otter pup. As lead responder for the Homer branch of the Alaska SeaLife Center's (ASLC) Marine Mammal Stranding Network (MMSN), this wasn't her first call to assist with critters that were out of their element. After quickly finding a colleague to run the chemistry lab in her absence, she says with a laugh, "I ran out in my dress, tights and new boots. Not exactly rescue gear."

"[The otter pup] was screaming, which is a good thing," Boege-Tobin explains. They hoped those vocal abilities, so effective in rallying rescuers, might summon the pup's mother. With permission from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and ASLC, Boege-Tobin along with cooperating neighbors, MMSN volunteers and a KBC Semester by the Bay student were able to kennel the pup and monitor her at the water's edge beside Mud Bay while she continued to call. They hoped for an ideal outcome-a reunited pup and mother-since a young sea otter pup raised in captivity can never be returned to the wild; the pups require intensive attention from caregivers and are no longer good candidates for reintroduction once they reach maturity.

Boege-Tobin speculated that the pup wandering down the road may have been separated

from its mother in a recent storm. There was no Hollywood reunion to be had, though.

When the mother no-showed, a KBC student and staff member drove the pup to Soldotna

for a hand-off to ASLC Rescue & Rehab staffers from Seward while Boege-Tobin got back

to work. The young pup will be tended to at the center's I.Sea.U critical care unit

until USFWS determines her next chapter. (ASLC reported on Oct. 28 that the pup is

looking good and doing well, enjoying the addition of some clams into her diet of sea otter formula.)

Boege-Tobin speculated that the pup wandering down the road may have been separated

from its mother in a recent storm. There was no Hollywood reunion to be had, though.

When the mother no-showed, a KBC student and staff member drove the pup to Soldotna

for a hand-off to ASLC Rescue & Rehab staffers from Seward while Boege-Tobin got back

to work. The young pup will be tended to at the center's I.Sea.U critical care unit

until USFWS determines her next chapter. (ASLC reported on Oct. 28 that the pup is

looking good and doing well, enjoying the addition of some clams into her diet of sea otter formula.)

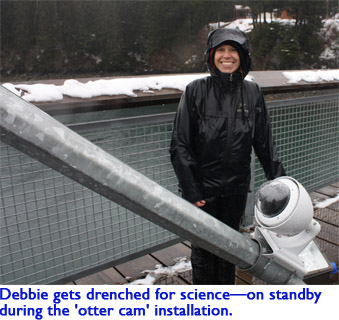

'Otter Cam': Kasitsna Bay otter antics on display for KBC researchers

Boege-Tobin has extensive otter-handling credentials. She's wrangled them on two continents-giant

otters in Guyana, South America, North American river otters in Missouri and sea otters

in Kachemak Bay, Alaska, where she assisted USFWS with live-captures and tagging.

As a doctoral student at University of Missouri-St. Louis, she listened to giant otters

with sophisticated acoustic equipment, she live-trapped river otters and implanted

tracking tags and she smelled, well, some things not every non-biologist gets to smell

(otters are olfactory communicators and will scent mark at latrine sites and along

frequently used waterways). As a professor and researcher, she's also recently begun

monitoring some of Alaska's coastal river otters with a sophisticated motion-activated

"otter cam" mounted to a dock in Kasitsna Bay.

The Kasitsna Bay otters are great potential research subjects for Boege-Tobin's undergraduate

student researchers at KBC. Kasitsna is home to a research facility jointly operated

and recently remodeled by NOAA and UAF. "It's an amazing place to take students,"

Boege-Tobin says, citing the lab facilities and dormitories they're able to use. For

the past few years, she's taken groups of students along to study the intertidal zones

of both Kasitsna and nearby Jakolof Bay. The data logs they compile in partnership

with other community agencies are a sort of finger-on-the-pulse to monitor the health

of greater Kachemak Bay.

The Kasitsna Bay otters are great potential research subjects for Boege-Tobin's undergraduate

student researchers at KBC. Kasitsna is home to a research facility jointly operated

and recently remodeled by NOAA and UAF. "It's an amazing place to take students,"

Boege-Tobin says, citing the lab facilities and dormitories they're able to use. For

the past few years, she's taken groups of students along to study the intertidal zones

of both Kasitsna and nearby Jakolof Bay. The data logs they compile in partnership

with other community agencies are a sort of finger-on-the-pulse to monitor the health

of greater Kachemak Bay.

Those intertidal studies introduced Boege-Tobin and her students to the sea otter populations in and around Kasitsna. With some grant funding from Kenai Peninsula College and its Community-Engagement and Service-Learning mini-grants, Boege-Tobin was able to engage students in more hands-on research. And last year they installed the new motion-activated camera. The coolest part? The Kasitsna Bay otter cam can be controlled from miles away-they can reposition, pan, zoom, whatever they need to do to best capture otter behaviors, from within their home lab at KBC, across the bay from the active otters. The receiver at KBC stores the images for study by professors and students. At present they're working out a few connectivity bugs, but their 24-7 eyes-on-the-otters observer is in place taking notes, ready to provide the raw data for researchers who have proposed several projects.

In the pipeline for biology students at KBC are scent discrimination studies, foraging

assessments, scat analyses and a study of play behavior (the Kasitsna Bay otters are

known for enjoying a good romp in the fish totes on the dock, given the opportunity).

All endeavors will be assisted by the candid camera. Boege-Tobin is excited to lend

her otter expertise to students as they further develop their projects. She also hopes

to use the cam to eventually study the sea otters, whales and harbor porpoises that

frequent Kasitsna Bay, linking it to hydrophones in the waters nearby.

In the pipeline for biology students at KBC are scent discrimination studies, foraging

assessments, scat analyses and a study of play behavior (the Kasitsna Bay otters are

known for enjoying a good romp in the fish totes on the dock, given the opportunity).

All endeavors will be assisted by the candid camera. Boege-Tobin is excited to lend

her otter expertise to students as they further develop their projects. She also hopes

to use the cam to eventually study the sea otters, whales and harbor porpoises that

frequent Kasitsna Bay, linking it to hydrophones in the waters nearby.

Pack your play clothes for Semester by the Bay

Think all the cool hands-on science is just for lucky Kenai Peninsula residents? Nope.

Boege-Tobin has helped to create KBC's new Semester by the Bay program. It's designed

to allow students from any university or college the chance to roll up their sleeves,

try on some XtraTufs (for those folks who don't already own them as a wardrobe staple)

and learn marine biology in a series of courses they'll be able to transfer back to

their home campuses. This fall KBC and Boege-Tobin welcomed the second cohort of Semester

by the Bay students, who also get the chance to partner up with some community agencies

to assist with research and service learning projects. In exchange, the community

agencies subsidize a portion of the students' housing during their stay in Homer.

Last fall, Semester by the Bay students spent time on the water, in the lab and along

the coastline. Boege-Tobin vividly recalls a kayaking trip in the bay with students

when they were delighted by some unexpected visitors-humpback whales surfacing to

lunge feed, a once-in-a-lifetime close encounter for most people. "We were looking

at the thousands of beautiful sea jellies in the bay, and we thought that was cool,

but the whale experiences were absolutely exhilarating!"

Last fall, Semester by the Bay students spent time on the water, in the lab and along

the coastline. Boege-Tobin vividly recalls a kayaking trip in the bay with students

when they were delighted by some unexpected visitors-humpback whales surfacing to

lunge feed, a once-in-a-lifetime close encounter for most people. "We were looking

at the thousands of beautiful sea jellies in the bay, and we thought that was cool,

but the whale experiences were absolutely exhilarating!"

This fall, students spent a great deal of time on the water with faculty observing sea otters with Angie Doroff (Kachemak Bay Research Reserve), observing harbor seals, sea birds and in the lab with Craig Matkin, Olga von Ziegesar and Dan Ohlson (North Gulf Oceanic Society) learning about acoustics, photographic identification techniques and behaviors of humpback whales and orca.

The afterlife of whales

Sometimes Alaskans ask a lot of their neighbors-can you spare some firewood or canned

salmon? Can you make sure my pipes don't freeze while I'm out of town? But Homer's

Devony Lehner and Tom Taffe get a gold star for saying yes to some odd requests from

Boege-Tobin and KBC. Specifically, "Can we bury a whale carcass or two on your property?"

KBC students, including the two Semester by the Bay cohorts (2011 and 2012), have been fortunate to accompany Boege-Tobin and community partners when reports of a dead whale in the bay come in. Last year's students assisted with a Stejneger's beaked whale necropsy. That particular whale species isn't well understood, so the chance to study a beached specimen can be valuable to researchers and an unforgettable experience for biology students.

With permission from NOAA, the whale carcass was given to KBC for further study after

the necropsy was completed. That's where Lehner and Taffe's generosity came into play.

With a little advice from Homer's "bone man," Lee Post, owner of a local bookstore

and skeleton articulation expert, and Melissa Reichmann, biological artist/museum

exhibit fabricator and developer and owner of Nature Tales Studio, students planned

to bury the carcass in manure on the Lehner/Taffe property so the microscopic flora

and fauna could go to work cleaning off the bones in time for this year's students

to dig up the skeleton and articulate it for study and display at KBC.

With permission from NOAA, the whale carcass was given to KBC for further study after

the necropsy was completed. That's where Lehner and Taffe's generosity came into play.

With a little advice from Homer's "bone man," Lee Post, owner of a local bookstore

and skeleton articulation expert, and Melissa Reichmann, biological artist/museum

exhibit fabricator and developer and owner of Nature Tales Studio, students planned

to bury the carcass in manure on the Lehner/Taffe property so the microscopic flora

and fauna could go to work cleaning off the bones in time for this year's students

to dig up the skeleton and articulate it for study and display at KBC.

Their project piqued the interest of another UAA biologist, Professor Fred Rainey, D.Phil., director of the Department of Biological Sciences on UAA's Anchorage campus. He flew down to Homer to take samples of the soil around the interred whale skeleton to determine just what flora and fauna were responsible for the rapid decomposition, specifically of the blubber.

Boege-Tobin reports that when last year's biology students dug up a previously buried gray whale skull, left pectoral flipper and scapula, they were pleased to find clean bones, in need of just a quick rinse at the local car wash. Last year's Semester by the Bay cohort articulated the gray whale flipper, while this year's students have been busy articulating and mounting the gray whale skull outside the new KBC Bayview Hall for permanent educational display. Currently, Semester by the Bay and KBC students are articulating the entire beaked whale skeleton in the lab, again with the help of Lee Post, artist Melisse Reichmann and KPC's facilities guru Larry Staehle.

This year's biology students also were insiders on the recovery and necropsy of a beluga whale recovered with the help of a spill response tug boat in Cook Inlet's Nikiski Bay. With Professors Rainey and Boege-Tobin on hand, and with permission from the proper federal agencies, the students buried the beluga carcass post-necropsy on the Lehner/Taffe property (maybe they should get two gold stars for their commitment to science education and all of its accompanying fragrances). Rainey was able to take some preliminary samples of the manure mixture surrounding the carcass and also place temperature probes to monitor the changing soil temperature at the burial site.

So, while we may not have an acceptable answer to the spiritual implications of the question, "Where do whales go when they die?," we can say with certainty that some of them are enriching science education in Alaska.

'I love my job.'

"I knew this would be a fantastic place to live and to work with students," Boege-Tobin

says of Homer. "I love my job. I love being able to engage the students from the beginning

100-level classes all the way through."

Boege-Tobin is looking forward to mentoring more biology students in the future, including

some senior thesis students, as well as spending some time on her own research projects.

She's been collaborating with several local agencies on ongoing projects in Kachemak

Bay outside of her teaching and MMSN roles. It keeps her pretty busy.

Boege-Tobin is looking forward to mentoring more biology students in the future, including

some senior thesis students, as well as spending some time on her own research projects.

She's been collaborating with several local agencies on ongoing projects in Kachemak

Bay outside of her teaching and MMSN roles. It keeps her pretty busy.

With her background in marine mammal research (she worked with dolphins and dolphin communication in the Florida Keys and off the West Banks of the Bahamas as a master's student, then was snapped up post graduation to work with marine mammals at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago), Boege-Tobin was excited to make the move to Homer in 2006. "My husband moved here sight unseen," she says. He knew if she loved it, he'd love it, and they're happy their son gets to enjoy an Alaska childhood, keeping pace with the rest of the Boege-Tobin family (including the dogs!) as they enjoy all that their Alaska "backyard" has to offer--skiing, fishing, hiking and whale watching are at the top of the list.

Although there's no shortage of cool jobs and interesting people in Homer, we suspect Boege-Tobin might just blow the other parents out of the water if she's invited to Career Day at her son's school one day. After all, chances are if Boege-Tobin stops off at home with a dog kennel in the back of the car, it probably contains something a little more exotic than a cocker spaniel.

Find out more about Boege-Tobin's adventures with Semester by the Bay students on their Facebook page. You can also read more about Semester by the Bay on their website.

"Research by the bay: a closer look at otters and whales" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Research by the bay: a closer look at otters and whales" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.