Project 49: Getting paid $165 a month? 'I thought that was pretty wonderful.'

by Tracy Kalytiak |

When Beulah "Bee" Marrs Parisi was a 10-year-old growing up in northern Minnesota, she began reading a novel by James Oliver Curwood and immediately fell in love with the magnificent untamed Far North world it swept her into.

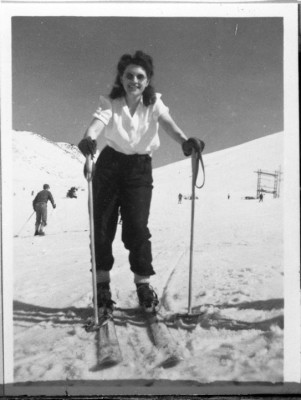

Beulah "Bee" Marrs Parisi skis in Alaska in the spring of 1945. (Beulah Marrs Parisi Collection, Archives and Special Collections, UAA/APU Consortium Library)

"I decided I was going to go to Alaska for a vacation," she wrote. Parisi lost her mother the following year. She finished school, attended college and graduate school and launched a career as a schoolteacher before, 19 years later, finally realizing her girlhood dream. The former USO volunteer, hostess and founding member of the affectionately dubbed "Bee Hive" house in Anchorage gathered snippets from her four and a half years in Alaska into a collection of papers and photos she donated to the UAA/APU Consortium Library archives in 1994.

Finding a niche in Alaska

In those papers, Parisi recounted her Aunt Grace's insistence that she buy a return ticket from her trip to Alaska in June 1941. "She was flabbergasted that I had not done so, and would not hear of my going up to that 'Wilderness' possibly having something dreadful happen to me and get stranded and have no way to get home," Parisi said.

Parisi studied as much as she could about Alaska before booking passage on the S.S. Baranof from Seattle to Seward. Aboard the Baranof, Parisi met other women who were also traveling to Seward and then taking the train to Anchorage. They played shuffleboard, learned to dance the varsovienne-"a stately folk dance"-and tried to look out for passing birds. "Cleaning our clothes from overhead seagulls took quite a bit of time some days," she wrote.

Once in Anchorage, Parisi eventually moved into a house dubbed "The Bee Hive" because the names of several women initially staying there-Beverley Pettyjohn, Blanche Kerr, Beulah Marrs-started with the letter "B." (Another woman named Polly Petty coined the house's nickname; she was considered an honorary "B.") They shared all the cooking, cleaning and laundry tasks, paying about $60 a month each for rent.

"I guess Bev and I worked out the main principles of our house," Parisi wrote. "We agreed that we would always be a family. ... We did a lot of entertaining and received food stuffs from time to time, especially game, and were guests 'out to dinner' but there was never any refunding of any kind."

Beulah Marrs (later Parisi) stands next to a Bristol Bay Air Service airplane just before her first flight to Dillingham, in 1942. Parisi worked for the company. (Photo from the Beulah Marrs Parisi Collection, Special Collections and Archives, UAA/APU Consortium Library)

The women threw themselves into life in Alaska. They hiked, picnicked at Fire Lake, camped, skied and played in the snow. "Almost every Sunday all winter long, we were outdoors, all the years I was in Alaska," Parisi noted.

Relishing independence

Some of the women went up to Alaska with the express purpose of looking for work.

"That was not my original intention," Parisi wrote. "Since I fell in love with Alaska from the very first I decided to look for a job. The employment office was the place everyone went for information."

Bristol Bay Air Service needed a bookkeeper.

"When questioned, I told them no, I had never done any bookkeeping, but I had my degree, had taught arithmetic which included simple bookkeeping and done two quarter hours in math in graduate school," she wrote. "The attendant thought I could handle the job and sent me over."

Parisi kept track of expenses and income, which included weighing baggage for passengers who were primarily working fishermen traveling down to Bristol Bay. Shortly after she started working, the Morrison-Knudsen Company started using the company's three planes to fly men down to their jobs of building airports.

"I acted as sort of a 'Mother Hen' for many of the men that we flew down to the Bay," she wrote. "They sent requests up with the pilots for various items: underwear, gloves, pants, socks, etc. I mailed their letters and did other errands and genuinely enjoyed my work."

The Bristol Bay office was located about a block and a half east of a spot in Anchorage dubbed "The Corner"-the intersection of Fourth Avenue and E Street.

An airplane stands in the snow at a field believed to be Merrill Field, its engine covered with a tarp and a heater aimed at the plane. (Photo from Beulah Marrs Parisi Collection, Special Collections and Archives, UAA/APU Consortium Library)

Fourth Avenue, then, was the main street of the city and the business district stretched out on both sides for about 10 to 15 blocks. At "The Corner" were Loussac's Drug Store; Hewett's, "an ice cream, photos and everything else store;" the Bank of Alaska; and the city hall and military police station. Two blocks west were the new federal building and post office, between F and G streets. More than two blocks away, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and H Street, stood the eventual Bee Hive.

"There were so many bars in town we used to say they were every other business," she wrote.

The owner of Bristol Bay Air Service was pleased with Parisi's work. "At the end of the month when he had me make out my check for him to sign he said make it at the rate of $165.00," she wrote. "I thought that was pretty wonderful."

School would be starting soon in Minnesota. Parisi had a contract to teach there. Seeing that paycheck prompted her to send a letter to her principal in Richmond, Minn., asking for a year's leave of absence or a cancellation of that contract.

"I explained to him that I was enjoying Alaska so very much and with the raise I could then afford to stay," she wrote. "He canceled my contract."

The following spring, she took the chance to fly to Dillingham, though wartime precautions wouldn't permit her to create keepsakes from the flight: "The unfortunate part of taking airplane trips is that no pictures can be taken from the air now," she wrote.

World War II raged toward Alaska, casting a shadow over Parisi's life in Anchorage. In June 1942, the Japanese bombed Dutch Harbor and occupied the Aleutian islands of Attu and Kiska. Who knew what they might do next?

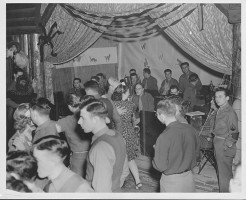

Women dance with servicemen at the Halloween 1943 dance in Anchorage's USO building. (Photo from Beulah Marrs Parisi Collection, Special Collections and Archives, UAA/APU Consortium Library)

"Thanks for signing the bank card," Parisi wrote 10 days after the Dutch Harbor raid, in a letter to a Minnesota relative she marked, "Confidential." "In case anything like a bombing happens here, I just want to have my personal property and case where someone can get some use of it without having to spend all of it in legal expense. If you get any message of my death, write to the bank and have them send the money to you. There won't be much. I carry about $300.00 in my checking account most of the time and have less than $200.00 in the savings account now."

Boosting morale

Because of the war and Alaska's strategic importance, servicemen swarmed to Fort Richardson in response to the Japanese threat to the Aleutians and to protect the Territory. The United Service Organization reached out to provide entertainment and recreation for these thousands of men serving their country far from home. The women of the Bee Hive took part in what became known as the USO's "Girls Service Organization," volunteering to help at the USO's "Friendly Log Cabin" at the corner of Fifth Avenue and G Street. Parisi served as the group's president and, in 1944, became the Friendly Log Cabin's official hostess.

A group of women arrive at Fort Richardson dressed in formal attire, including USO volunteers and "Bee Hive" residents Polly Petty, Beulah Marrs (later Parisi), and Beverley Pettyjohn. (Photo from Beulah Marrs Parisi Collection, Archives and Special Collections, UAA/APU Consortium Library)

The women kept busy planning and organizing USO activities between 1942 and 1945, when the war ended. They played table tennis and listened to music with the GIs, served coffee and pie, and decorated the Cabin for countless dances, shows like "Bonanza Days" and parties with a state theme aimed at gathering together men who were from a given state.

Parisi's future husband, Pete Parisi, was stationed in Alaska with the headquarters squadron of the 11th Fighter Command during the war. He was one of the GIs on the committee organizing the New York-themed event.

"We worked together," said Parisi, 102, who now lives in a retirement community in the Lower 48. "Back then, we put the tall girls with the tall boys. He was short, I was short. He said, 'Guess I'm going with you!' I said, 'I might go if you asked me!'"

The two decided to marry. Four and a half years after arriving in Alaska, Parisi boarded a converted Army truck that would take her down the Alaska-Canada Highway and on to the next phase of her life: marriage to Pete Parisi, the births of their four children, a move from Minnesota to Oregon and a career volunteering for her church and working as the librarian for its school.

Parisi never returned to Alaska. "I miss it," she said, her voice wavering. "I miss the whole thing."

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Project 49: Getting paid $165 a month? 'I thought that was pretty wonderful.'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Project 49: Getting paid $165 a month? 'I thought that was pretty wonderful.'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.