‘We’re at the ready’: UAA researchers study coronavirus in midst of outbreak

by Matt Jardin |

On the evening of Tuesday, Jan. 28, a plane evacuating 201 Americans from Wuhan, the Chinese city at the center of the recent coronavirus outbreak, made a pit stop in Anchorage to refuel before continuing to its final destination in Southern California. For many Alaskans, this news marked the first time having to confront the effects of coronavirus. But for several UAA researchers, studying coronavirus has been all in a day’s work for more than 15 years.

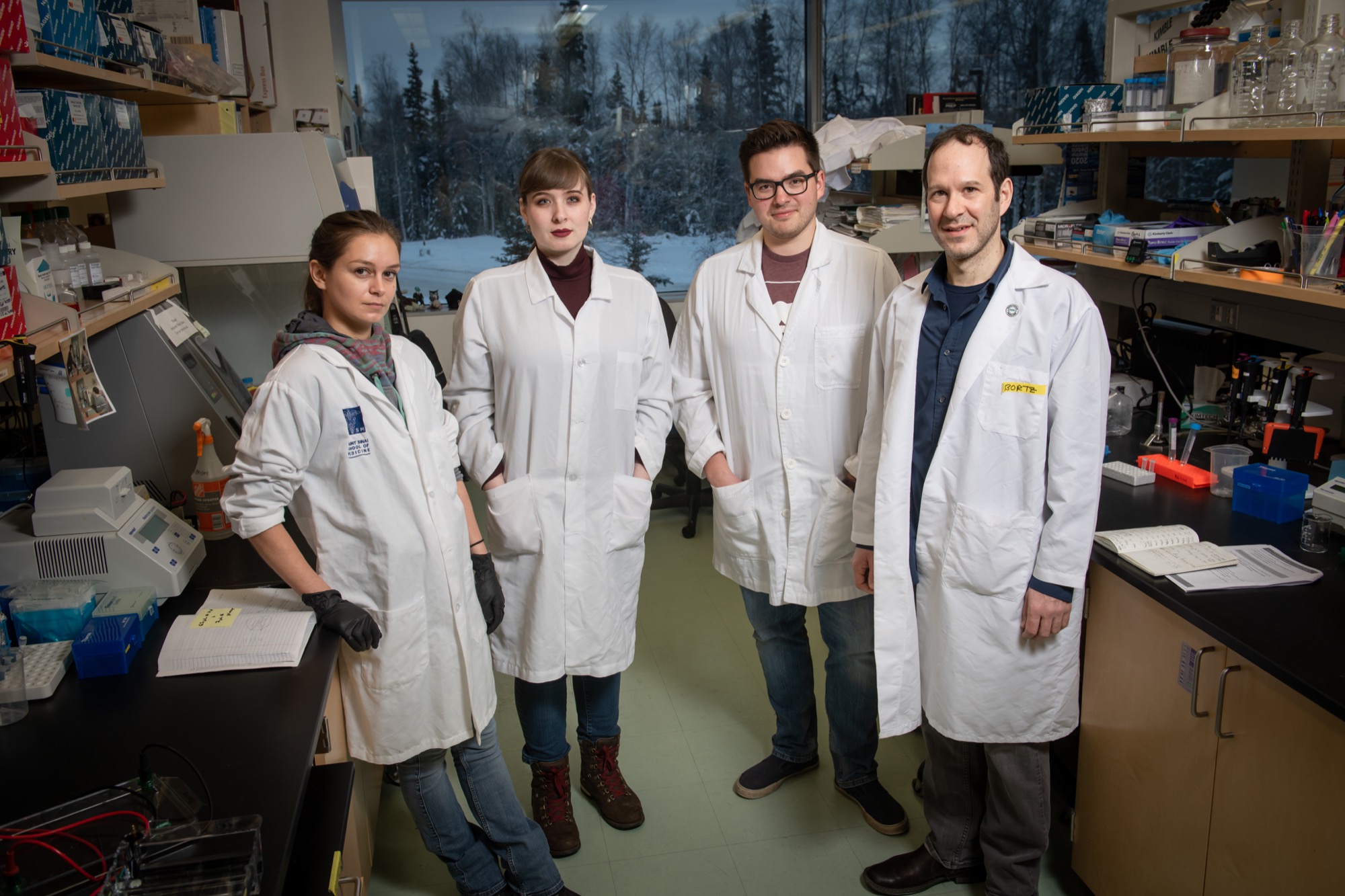

Led by UAA Department of Biological Sciences Associate Professor Eric Bortz, Ph.D., his team’s current coronavirus research is a progression of work started in 2014. Back then, UAA researchers swabbed bats in Southcentral Alaska to search for traces of various diseases, including coronavirus.

Bats are ideal for studying coronavirus due to their status as a common reservoir of its strains. Mutated coronavirus strains jumping from bats to humans are known to be the cause of the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak in 2003 and the MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) outbreak in 2012.

“Chance favors the prepared mind,” said Bortz. “Our ability to understand this new coronavirus is because people have been working on coronaviruses in bats and human populations for a long time. Really since SARS broke in 2003, it was put on the radar as a potential novel human epidemic virus in a way it hadn’t really been before. Because of that, we’ve been looking for bat coronaviruses in Alaska and developing tools that can then be applied to the novel coronavirus or other emergences of viruses out of nature.”

News of the recent coronavirus outbreak specifically refers to a particular strain, officially known as the novel coronavirus or 2019-nCoV, which, at the time of this writing, has more than 24,000 confirmed cases in China and 11 confirmed cases in the U.S.

Working under Bortz to learn as much as they can about the novel coronavirus are graduate student William George, doctoral student Maile Branson and research professional Elaina Milton.

After researchers on the 2014 bat project were able to sequence the discovered coronavirus genome, George joined the project as a graduate researcher in 2018 where he began analyzing the surface spike glycoprotein and comparing the similarities with other known coronavirus strains. He concluded that its potential to become more infectious wasn’t likely due to key similarities with other identified coronavirus strains, particularly one found in Colorado.

On the current team, George is taking an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” approach by applying his established methodologies on coronavirus genomes that more closely resemble the strain from recent news.

“What I’ve been doing is analyzing next generation sequencing data to see if I can extrapolate the coronavirus and bioinformatically piece it back together,” said George. “Once that occurs, you can look for novel mutations and build a phylogenetic tree and go, ‘aha!’ Here are the coronaviruses we know and here’s how they can branch off into something else. How the Wuhan coronavirus comes into play, since we have these protocols for sequencing and surveillance, we can take them and apply it to Wuhan 2019-nCoV.”

In addition to George’s prior sequencing work, Branson, whose area of study involves influenza, can apply what she knows about how viruses can jump from species to species and how they can cross vast distances.

“There are many different subtypes of influenza,” said Branson. “Some of them can infect people and some of them prefer birds, but there’s actually quite a bit of mixing. Bird migration and animal movement are what drive our flu season. So in looking at influenza specifically in birds, it could precipitate a pandemic event or strain at any point in time.”

By continually surveilling and sequencing coronavirus, the Bortz lab hopes to learn how it might mutate, like whether it will become more or less contagious. Once they get a clearer picture of the novel coronavirus structure, they may be able to discover possible preventative measures.

“If somebody has the common cold coronavirus, does that give any cross-protection against the new one? If somebody survived SARS, do they have antibodies that might block or dampen infection by the novel coronavirus? So those are the things we’re thinking about and communicating with the scientific community,” said Bortz.

A global-scale outbreak, of course, requires an equally global effort to study. Using Twitter, Bortz and company have been collaborating with researchers around the world on their coronavirus findings, giving a whole new meaning to going viral.

More formally, the team has partnered with the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) to standardize, catalog and make accessible coronavirus data to everyone around the world, with the hope of painting a clearer picture of regional coronavirus variants and contributing to a global pandemic response plan.

“Say Will designs additional primers and applies what he learned from the bats to the novel coronavirus. We haven’t tested those primers because we don’t have novel coronavirus samples here in Alaska,” said Bortz. “If there’s a mismatch, it gives you false positives or negatives, or maybe they just came down with a cold or the flu. So we have to update the sequences constantly because the virus mutates. So analyzing the sequence and having as many minds working on this is a great thing.”

Handling all of the team’s invaluable data is Milton, who has earned the title of data guru from Bortz. She also serves as the point of contact for the Bortz lab, offering clarity amid a lot of ambiguity and sensationalism.

“I want to let Alaskans know that we’re here at UAA and we’re ready to handle this if it comes,” said Milton. “We have an offshoot of the CDC here in Anchorage and we have confidence in the public health department to also handle it, so we’re at the ready.”

Written by Matt Jardin, UAA Office of University Advancement

"‘We’re at the ready’: UAA researchers study coronavirus in midst of outbreak" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"‘We’re at the ready’: UAA researchers study coronavirus in midst of outbreak" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.