UAA professor asks, 'Have you seen a snake in Alaska?'

by Keenan James Britt |

Alaska is renowned for its wildlife. Millions of travelers visit the state each year to view wildlife species like bears, moose and whales, and Alaska’s salmon and halibut fisheries provide ample sport and subsistence opportunities for residents and visitors.

The state is also famous for the wildlife it is not home to. Alaska, it is often said, is not home to any snakes. According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) no snakes or other terrestrial reptiles live wild in Alaska; the only reptiles found in the state are species of sea turtles that can be occasionally seen in Alaska’s coastal waters.

However, this situation could be changing.

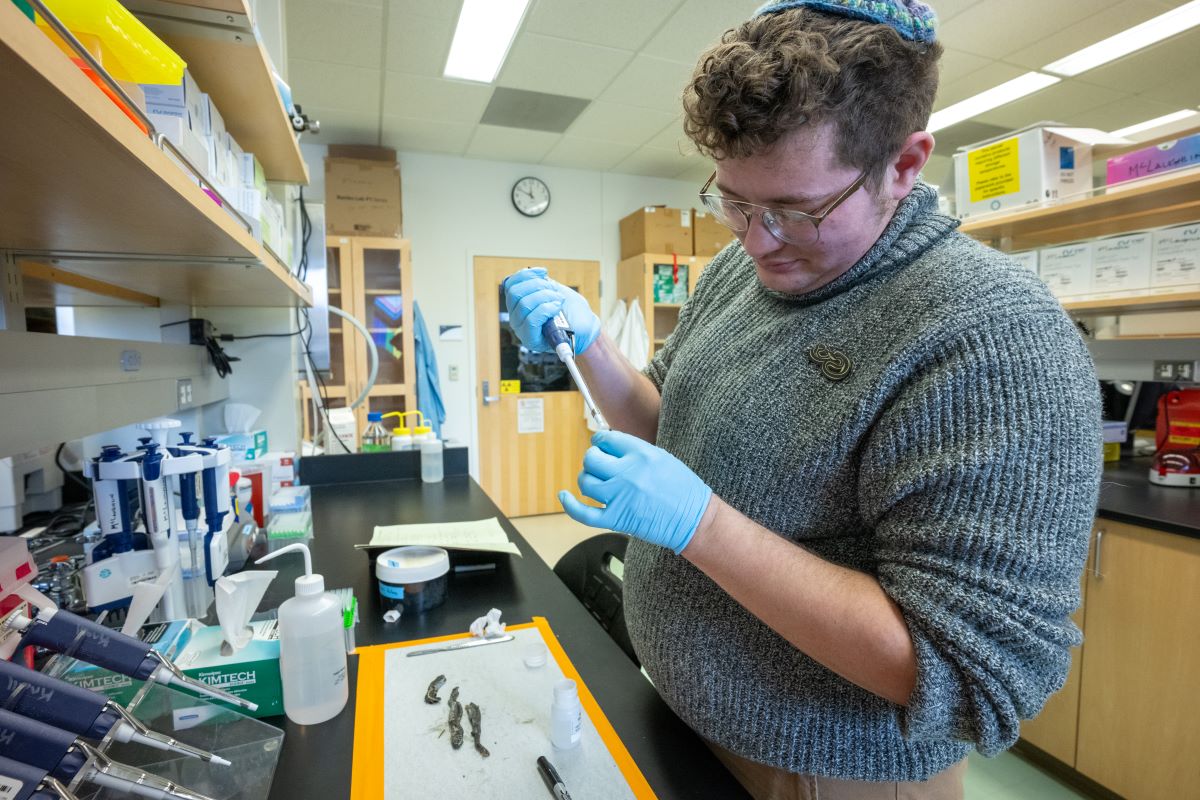

In April, a deceased snake was discovered in a hay bale that had been shipped on a barge from Washington state to Southcentral Alaska as livestock feed. The remains of the snake were sent to UAA’s Anchorage campus for analysis in the McLaughlin Lab before being sent on to the ADF&G. The remains were identified as those of a wandering garter snake (Thamnophis elegans vagrans).

Jess McLaughlin, Ph.D., assistant professor in UAA’s Department of Biological Sciences and the lab’s principal investigator, had been contemplating the legitimacy of the ‘no snakes in Alaska’ claim since joining UAA last fall.

“Wheels had been turning since I got the job offer,” McLaughlin said. “But the finding of the garter snake was like, ‘No, this is not just a theoretical thing. It's happening.’”

While the garter snake that ended up at the lab was dead by the time it arrived in Southcentral Alaska, McLaughlin suspects that snakes and other reptiles may be able to arrive in Alaska alive and well in the near future.

“We’ve had a lot of mild winters, and they’re only getting more mild,” McLaughlin explained. “So the chances of an introduction actually leading to an established population that can sustain itself if we get them arriving alive is only increasing.”

Elusive snake sightings have been reported throughout Alaska’s history

McLaughlin and some of the students in their lab are searching through historical newspaper archives for previous reports of snakes arriving in Alaska in the 20th century. The earliest report they have found so far goes back to a snake arriving in a hay bale in Fairbanks in 1916.

The idea to search historical newspapers arose from a conversation with James Evans, UAA’s chief of photography, who visited the lab to photograph the garter snake’s remains. “I started digging into this based on [something] James said, that snakes are unusual enough that when people find them up here they tend to end up in the newspaper,” explained McLaughlin.

The project gave McLaughlin and their students a unique opportunity to combine archival research with biology by searching through old newspapers preserved on microfiche.

“I find it actually really funny that in my lab we're doing this cool next-gen genomic sequencing, and also, I'm going to go spend my lunch break looking through microfilm,” McLaughlin said. “It's a cool example of how we can do biology. [...] It's not just going out and collecting samples. A lot of times, it is going back and digging through old publications to see this stuff.”

McLaughlin believes that it would be possible for garter snakes to establish a population in Southeast Alaska, noting that there are “a couple species of garter snakes in Canada that live in pretty comparable temperatures and climates, including some very close to the Alaska border.”

McLaughlin is currently researching reports of snakes found in Southeast Alaska during the mid-20th century.

“There was supposedly a specimen that was collected in 1957, down on the Taku River, but the specimen went missing at some point, and nobody's been able to confirm it,” explained McLaughlin. “And there [were] a lot of reports up through the late ’70s on the Stikine River, but nobody's been able to find them since.”

While some people in Alaska keep snakes as pets, McLaughlin believes that the snakes reported in Southeast Alaska in the 20th century must have been from a wild population, and not escaped or abandoned pets: “If we look at where these were being reported, these were almost certainly not dumped pets. Nobody's going up the Stikine River and dumping their pet garter snake.”

Involving the community in monitoring for amphibians and reptiles

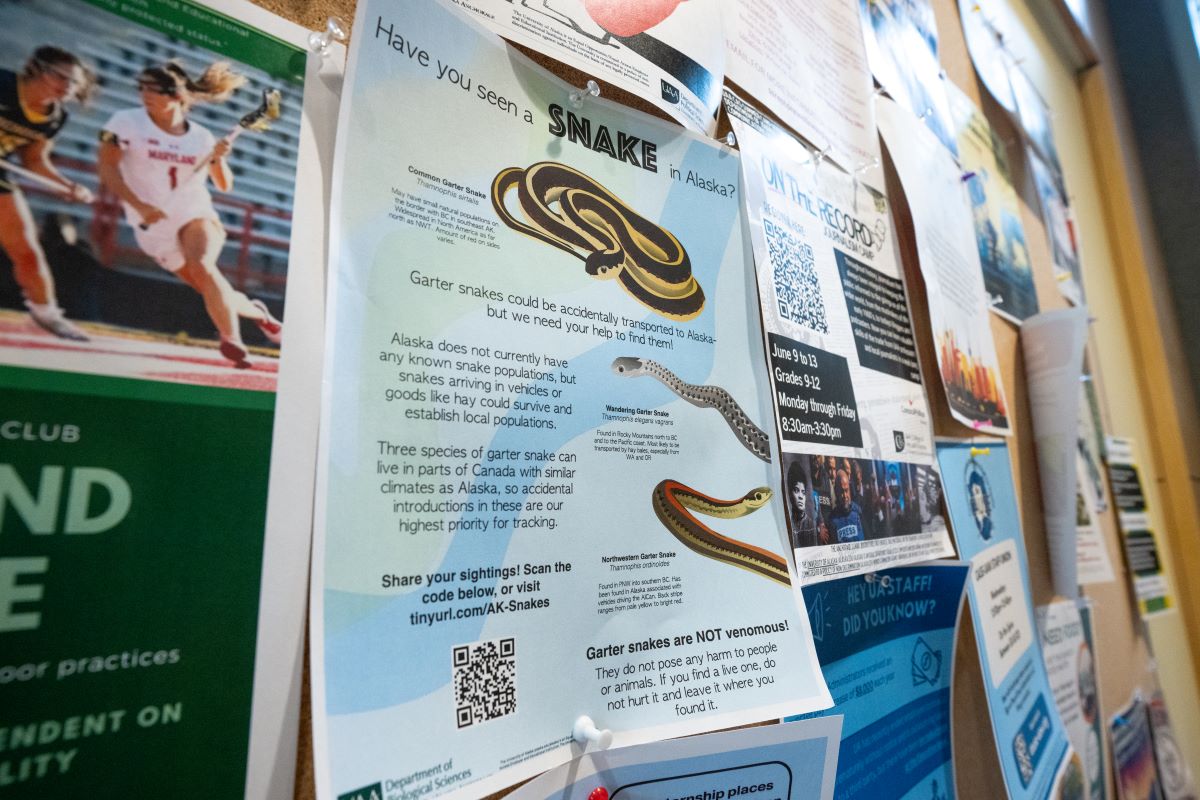

McLaughlin is seeking community involvement in identifying potential reptiles and amphibians in the state. They recently posted flyers on campus asking, “Have you seen a snake in Alaska?” The flyers contain a QR code that links to a snake observation report form.

“One of my plans is that I am going to try to hit every feed store in the Mat-Su and Anchorage area to put up these posters,” McLaughlin said, believing that there is a strong possibility that another garter snake will arrive via hay bales.

However, McLaughlin is aware that “single reports from people alone are not going to be enough to confirm anything.” They are interested in testing for the presence of new reptile and amphibian species in Alaska by taking samples of environmental DNA (eDNA) from bodies of water throughout the state. Samples of eDNA could confirm the arrival of new species in the state.

McLaughlin is in the process of launching a new project they call “Project SAlaMANDER” (Southeast Alaska Monitoring and Amphibian Detection with eDNA Resources). The project aims to collect data statewide on Alaska’s native amphibian species (like the wood frog or the rough-skinned newt) as well as monitor for the arrival of any new species of reptiles or amphibians, such as garter snakes, Siberian salamanders or American bullfrogs.

“If we start monitoring now, before we have confirmed populations, we’re going to be able to study the populations when they do get going,” McLaughlin said. “I think it’s a when, not an if.”

"UAA professor asks, 'Have you seen a snake in Alaska?'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"UAA professor asks, 'Have you seen a snake in Alaska?'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.