Biomining for rare-earth elements

by Keenan James Britt |

The rare-earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 transition metals on the periodic table of elements, which includes cerium and lanthanum. REEs are essential for manufacturing many modern electronic devices like cell phones, solar panels and EV batteries. Naturally, access to REEs is a major concern for economic vitality and national security.

As their name implies, REEs are not found in large, homogenous concentrations, but generally occur in compounds with other elements, known as rare-earth ores. Traditional methods for extracting these elements from the ore have relied on the use of strong acids to break down the compounds. However, using acids to extract REEs has certain drawbacks.

“REEs are critical components of modern technologies,” explained D’Lynn Gleason, a master’s candidate in biology. “Yet, their conventional extraction methods are both environmentally damaging and economically intensive.”

Last semester, Gleason defended her thesis ‘Binding Activity of Glacier Bacteria Towards Rare Earth Elements.’ Gleason was a master’s candidate in biology at the time, while also simultaneously serving as lab manager and an adjunct faculty member at Mat-Su College. During her thesis work, she experimented with using an alternative method to extract REEs from ore.

Gleason took an approach known as biomining, which involves using microbes to extract metals from ores. According to Gleason, “the field of biomining has gained momentum as researchers seek environmentally sustainable alternatives to traditional mining methods for critical minerals.”

During her project, Gleason turned to local materials for her experiments — both microbes and ores.

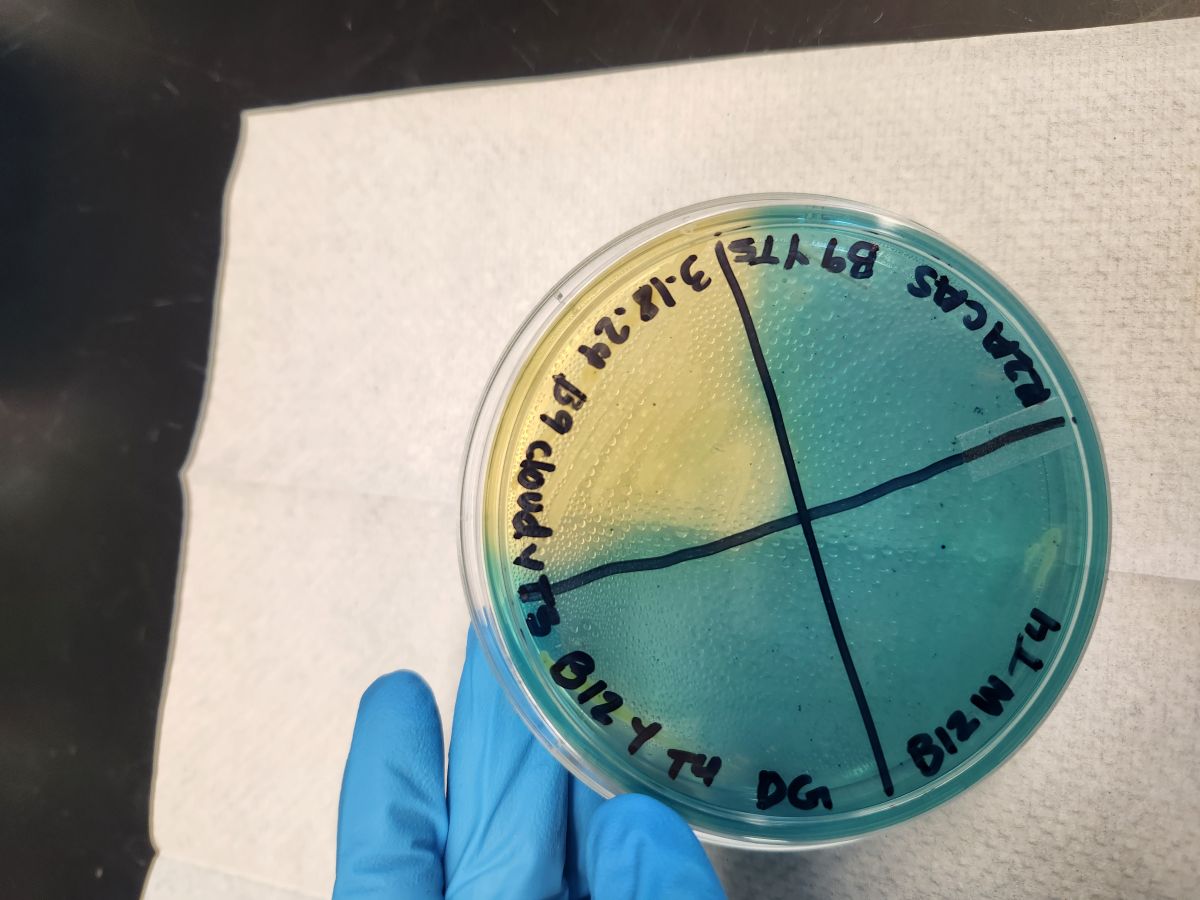

Gleason worked with microbe samples collected from glaciers in Southcentral Alaska, including from water and soil samples from Kennicott Glacier and Root Glacier in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. The samples were initially collected by a team led by Brandon Briggs, Ph.D., professor of biological sciences, during a June 2022 trip to collect microbes in the glacial meltwaters in Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark. The ores Gleason used were coal samples donated by Usibelli Coal Mine in Healy. Gleason noted that Usibelli coal “has relatively high concentrations of REEs” including scandium and yttrium.

“Science is 10% results, 90% character development,” Gleason said about the challenge of determining whether glacier bacteria excrete compounds that can break down ore to bind to metal ions. “It took a good amount of time to actually isolate the bacteria, and then to develop the test to see if there's any type of metal binding going on. It took some trial and error as well.” Ultimately, Gleason was able to use microbes to extract REEs from the Usibelli coal samples; she concluded that “glacier bacteria are capable of binding and extracting REEs.”

Gleason’s research has practical applications that could provide a major boon to Alaska’s economy in the future.

“Alaska has a lot of rich mineral sources [but] we don't currently have mining here for rare-earth elements. That coal has relatively high concentrations of rare-earth elements that just aren't being taken advantage of right now,” Gleason explained. “We can't traditionally mine them with acid, because they're just at such small concentrations that it wouldn't be feasible or wouldn't be efficient. That's what's driving this question of ‘how can we develop a system where we can extract those minerals and take advantage of the rare-earth elements without having any drastic effects on the environment?’”

"Biomining for rare-earth elements" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Biomining for rare-earth elements" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.