Chris Barnett's biology graduate thesis earns national recognition

by Kathleen McCoy |

Congratulations are in high order for Alaskan and UAA alumnus Chris Barnett. He recently

earned his master's degree in biological sciences from UAA; the thesis he wrote just

won national recognition from the Western Association of Graduate Schools (WAGS).

Congratulations are in high order for Alaskan and UAA alumnus Chris Barnett. He recently

earned his master's degree in biological sciences from UAA; the thesis he wrote just

won national recognition from the Western Association of Graduate Schools (WAGS).

Stories like this are a joy to write because they are such good news. Who among us can't take a moment to enjoy the hard-earned achievement by one of our own?

But this story was even more fun to write and you'll learn why in a moment. First, let's do the drum roll and make the podium announcement.

Chris' winning master's thesis was titled "Williams Syndrome Transcription Factor is Critical for Neural Crest Cell Formation in Xenopua Laevis." (That, by the way, is Latin for the African Clawed Frog, an excellent model for studying human development.)

He and his work were named winners of the WAGS/UMI Distinguished Master's Thesis Award for Biological Sciences, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Life Sciences and Engineering. His thesis advisor was Dr. Jocelyn Krebs.

This award is a definite addition to his growing resume, Chris confirmed. On top of

a certificate, he receives a $1,000 check and an invitation to attend an awards ceremony

with Dr. Krebs in March in Tucson, Arizona. Very nice, indeed!

The additional pleasure in talking and writing about Chris comes from learning his

path to this achievement. He defended his thesis in October 2011 and then flew to

Texas to be near his girlfriend attending medical school there. He got a job working

at a community college setting up chemistry labs and busied himself applying for graduate

school. He's decided to pursue a higher degree in public health.

When we spoke by phone, I mentioned that I hoped his achievement would inspire other students, and hoped to frame the story that way. Just as Steve Jobs said in his famous Stanford commencement address, it's easy to connect the dots when you're looking backward; it's so much harder when you are navigating upstream trying to read signals and choose a direction. I hoped that a student struggling to find a path might be inspired by his success.

The minute I said it, Chris responded, "That would be me!" He, in fact, had wandered

a fair piece as he struggled to discover what he really wanted to do. Here's a bit

of his story.

He was born across the street from UAA at Providence Hospital to parents who came

here and fell in love with Alaska. He graduated from Dimond High School in 2001, intent

on going to medical school. The major he chose at the University of Colorado Boulder

was molecular cellular development biology-certainly a sound choice for a pre-med

student.

The only trouble was, he didn't really like the work. "And I had no Plan B," he remembered.

"I was too stubborn to change my major." He graduated, but didn't know what to do.

A ski resort job at Steamboat Springs filled in some of the time, but eventually he

drifted back to Alaska, still pondering career choices.

Maybe veterinary school? So he got busy working in veterinary offices and at the Humane

Society, and he decided to pick up a few extra classes from UAA before applying for

vet school.

"But in that process, I started to realize that veterinary school really wasn't what I wanted to do either," he said.

Now what? Here is where the dots begin to connect.

"I was taking a class from Doug Causey. I realized that with my major, I really should have some lab experience and I didn't have any. So I asked Professor Causey if he knew of any lab jobs. He said he'd check around for me."

And he did. The first opportunity was a volunteer slot in the Krebs' lab. His first tasks were literally emptying the trash and washing dishes. But eventually, he earned his way into a paying position as a "post-bacc." He helped grad students with their lab work, and eventually earned their trust and got more challenging lab tasks. He felt lucky to be earning the experience, but still wasn't sure what direction to go.

One day, Jocelyn Krebs told him that if he was interested in pursuing a master's in the biological sciences at UAA "we'd like to have you." He thought to himself, "I like working here. I might as well work toward something." And so, after a stint as a lab worker, he became a graduate student. He likes to say he "fell backwards into Jocelyn Krebs' lab."

More dots emerge for connecting.

Chris says the training he got in Dr. Krebs' lab was world-class. "As I got my legs under me, she was able to step back and let the learning process begin," he remembered. "But she was still very adamant about certain things."

One of them was the requirement that her graduate students write a thorough review

of all the primary research articles in their field. This not only grounds them in

their work, but has the added benefit of morphing into the first chapter of their

graduate thesis.

One of them was the requirement that her graduate students write a thorough review

of all the primary research articles in their field. This not only grounds them in

their work, but has the added benefit of morphing into the first chapter of their

graduate thesis.

Another was the "journal club" that met regularly. "We'd take a relevant article, and the whole lab would read it. Then we'd get together and talk about it." It helped set the framework for the lab's work generally, and his thesis, specifically. He said it is the kind of thing done routinely at major research labs around the country; he appreciates that Dr. Krebs brought the process to her lab at UAA.

"The expectations Jocelyn had helped me immensely," he said.

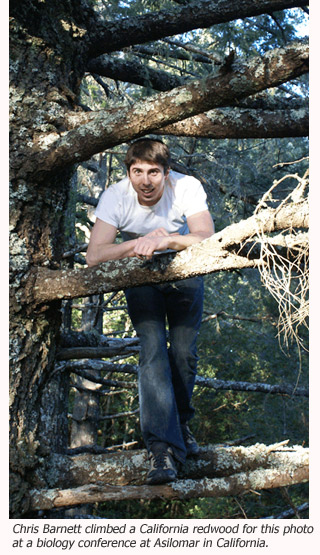

One story about those high expectations involved a conference she spotted and thought he should attend. It was a very prestigious annual meeting in Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island in New York, a spot where the world's experts on developmental biology come together for a two-week course.

"She told me about it, and I thought, 'Sure, that'd be great.'" And then he forgot all about it. The day before the application was due, she asked if he'd finished it. When he had to answer in the negative, she simply said, "You've got a day; better get it done."

He did, he got accepted, and the conference was a phenomenal experience for him. Things were really starting to click.

As he got more confident, he'd pitch research ideas to Dr. Krebs. "I'd come up with

these crazy ideas, and she'd say, 'OK. Good luck.'" And a few of his ideas worked

out really well, resulting in his successful thesis.

While he applies for graduate schools in public health, his work at the community

college puts him in frequent contact with undergraduates. Looking back, he thinks

of the undergrad years as so very different from his graduate school experience. He's

sympathetic with students tired of being lectured to, but he also knows what it takes

to push your way through the intensity of graduate school.

He remembers one college advisor who knew he was struggling with his undergraduate major. The advisor suggested he back off from it. "He told me, 'You have to be really interested in this stuff to be successful at it.'" Chris admits he was too stubborn to even consider that. Now he knows just what that advisor meant.

"This stuff is so obscure and very conceptual. It has its own esoteric language. You've got to be interested in it to get yourself to study as much as you need to to do well."

Another way to put it?

"If you're geeking out on it, you'll do fine."

Somehow, his own interest and Dr. Krebs' expectations were the perfect stew for Chris to immerse himself and grow into a researcher. "I couldn't have had a better PI than Dr. Krebs," he says.

Looking back now, all the dots connect.

NOTE: Read about Dr. Jocelyn Krebs Williams Syndrome research here. The "I" in this feature story is Kathleen McCoy, UAA Advancement .

"Chris Barnett's biology graduate thesis earns national recognition" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Chris Barnett's biology graduate thesis earns national recognition" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.