Rare earth

by Catalina Myers |

"Can I use the Bunsen burner?" says UAA sophomore Michael Martinez to a labmate as he pulls a tie-dyed lab coat from his bookbag and whisks around UAA Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Dr. Brandon Briggs' lab, on the third floor of the ConocoPhilips Integrated Science Building (CPISB). For the past two years Martinez, a biological sciences major, has been working, along with a handful of other students, to research how to extract rare earth elements from coal.

Biological sciences sophomore Michael Martinez studies ways to isolate rare earth elements from samples of Alaskan coal in assistant professor, Dr. Brandon Briggs' lab. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

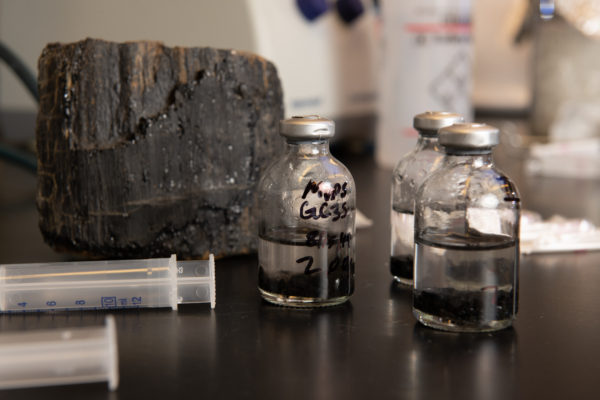

"Nerdy, I know," says Martinez grinning, referring to his colorful lab wear. Like a sous chef prepping his workstation, he assembles and arranges his materials on the black lab counter space before beginning his demonstration of the process of pulling a coal sample from tiny glass bottles.

With goggles, latex gloves and lab coat on, Martinez lights the Bunsen burner, holding the rim of a bottle up to the flame he's about to pull a sample from and carefully inserts a syringe. Slowly and methodically, he pumps the syringe back and forth - pushing out the excess air - and holds the glass bottle almost horizontal before extracting a 10-milliliter sample and depositing it into a tiny vial.

"You learn little tricks along the way," Martinez said of his process, explaining that like anything in life, practice makes perfect, even in the lab, where he estimates during the school year he spends eight to 10 hours each week on the third floor of CPISB.

The curious boy

Martinez was born and raised in Anchorage. His mother is Yupik, from the Village of Kotlik on Alaska's West Coast and his father is Mexican, originating from Central Mexico. For as long as he can remember, science has always been a passion.

"I've been doing science fairs since second grade, so I am pretty used to doing a lot of science projects," he says. "This [science] is very interesting to me because you're able to apply your curiosity and ask your questions while going through something that can be applied elsewhere."

Martinez attended Northern Lights ABC elementary school, which he says laid the foundation for his lifelong career in science. In high school, he was active in Service High School's Biomedical Career Academy, which introduced him to the world of research. As a 16-year-old, Martinez worked with Holly Martinson, assistant professor in UAA's WWAMI School of Medicine and was even awarded an Emperor Science Award for conducting cancer research. Most recently, Martinez, as an undergraduate, was awarded a first place prize in the Graduate Division Research Oral Presentation at the American Indian Science and Engineering Society's national conference, for his research in Briggs' lab.

Martinez says he is on the pre-med track - a goal he's had since he was young - and has participated in UAA's Della Keats summer research program after his senior year of high school. But, how did Martinez make the leap from biology to geology, landing himself an undergraduate research spot in Briggs' lab working with coal?

"I had talked to Dr. Ian van Tets - who listened to my story - and knew that I had research experience and hooked me up with a mentor," says Martinez, of being placed in Briggs' lab. "When I first heard the project of working with coal and bacteria, I thought, 'Wow, this is sort of out of the realm of oncology or biomedical research, but sure, I'll take a crack at it.'"

From oncology to geomicrobiology

"I had to learn about rocks because this was a total departure from the body," says Martinez. At first, he was completely out of his element and had to be a quick study on basic geology. "It kind of takes a while, stepping out of your field, but I think it was a good move and something I needed to open my eyes to the field of microbiology and geo-microbiology."

Martinez says that he is on the pre-med track with hopes of getting into UAA's WWAMI School of Medicine, but says his research in Dr. Briggs's lab has opened his eyes to the world of research. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

As a freshman, Martinez was invited to work in Briggs' lab, taking BIO 498, a course offered to seniors and within his first year under the mentorship of Briggs, presented at Alaska's American Society of Microbiology meeting at UAF. He won a second-place prize in the oral presentation category. For the remainder of his freshman year, Martinez took the rest of the BIO 498 courses - individual research - and once summer came, kept going. This past summer Briggs conducted a field camp near Gulkana to collect microbial samples for research during the upcoming school year.

It's exciting research he says, he and Briggs' other student researchers have started to make progress on what bacteria works. But, Martinez says he'd gotten ahead of himself and backs up a bit to explain what exactly they're researching and why it's so groundbreaking.

"We're looking at extracting rare earth elements, those are the lanthanides of the periodic table and the reason why they are so needed now and in the coming years, as we're developing new technology, renewable energy, machines that are more efficient and doing more space missions, we need these elements that are key in building these new engines, power accelerators and other stuff," Martinez says.

It sounds like science fiction, but it is the future, and Alaska could be at the forefront of a new resource industry that could deliver these rare earth elements found in our coal, to drive forward technological advances and space exploration.

"They're used in everything from military defense to electronics like your phone, and the reason why," says Martinez, "is that they have such powerful magnetic properties and high energy characteristics that kind of beat out all the other elements."

Over the summer, Martinez, along with a handful of Dr. Briggs' student researchers, conducted a field camp near Gulkana to collect microbial samples. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

Rare earth element extraction is nothing new. Martinez notes that nearly a decade ago, countries like China, Russia and India saw the value in extracting these elements for worldwide commercial use. During the 2010 tariff wars between the U.S. and China, rare earth elements were one of the top items the two countries argued over. In 2015, the U.S. closed its only rare earth elements mine (in California), leaving the country vulnerable in acquiring rare earth elements supplies for everything from technology to missile defense systems. It's a problem that Martinez thinks Alaska might be able to solve.

Martinez said the initial research was conducted by UAF to determine the rare earth element content in Alaska's coal and says that this has now become a joint project of sorts.

"What we're doing in our lab is trying to identify different bio-mining agents - different bacteria that are able to extract these rare earth elements, just as they are without producing hazardous materials or conventional methods," Martinez says. He explains that conventional mining techniques are inefficient and damaging to the environment. "We don't want to do that. If we can develop this - something new, something revolutionary - this will change the field of bio-mining."

An old industry with a new future

Martinez says he believes the research he and his fellow labmates are conducting may have the ability to transform Alaska's mining industry. And it's not just Martinez who believes that. He and Briggs have met with UAA's Business Enterprise Institute on how to make the jump from Briggs' lab to interested investors.

Martinez says that research can be repetitive and monotonous at times, but now that he is making major breakthroughs in his research, he's excited about his painstaking labor in the lab over the previous year. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

"We know these bacterias are working, it's just finding the next step of where to bring it now," says Martinez of the options researchers have once they're ready to go live, so to speak. "We can either publish papers, take it to a startup company or see if other universities want to partner with us."

In addition to investors who are interested in the commercial and industry aspects of his research, Martinez says several research institutions at universities across the country have reached out to him interested in joining the project. It's a lot for someone who is only in his sophomore year of college, but at the same time, not surprising since Martinez's career in science and research started really, when he was eight. It's been a lifelong passion that has built upon itself throughout the years, and although Martinez is just getting started, his rare earth elements research in Briggs' lab is a culmination of his lifelong pursuit of science.

"There are points where this is boring, it's not always fun, but what has been fulfilling for me is working toward a goal and finding after a whole semester, something that is working," says Martinez.

He's finished extracting his samples, about five, into little vials, which he places along with the glass bottles filled with coal samples back into the lab's refrigerator. Martinez removes his goggles, gloves and stuffs his lab coat back in his book bag, doing one last sweep of his station before heading out the door. It's been a long day, he gets to campus early and stays late after class, studying and finishing homework in the library. So the samples will have to wait another day when Martinez will work carefully and methodically to unlock the secrets the samples hold.

Written by Catalina Myers, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Rare earth" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Rare earth" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.