Spring 2013: Professor hopes to draw out the urban side of Anchorage

by Kathleen McCoy |

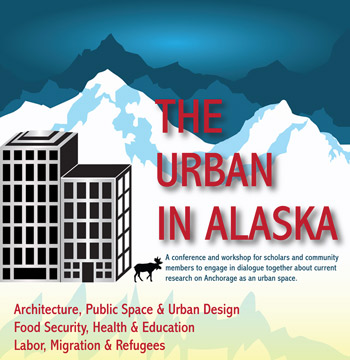

Friday, March 29, 8:30 a.m.-1 p.m.

The Den, UAA Student Union

Free and Open to the Public

Campus parking free on Fridays

I bet you can't name one person who admits they moved to Alaska so they could live in Anchorage.

Of course not. We come for the skiing, the snowboarding, the hiking-camping-fishing-everything

else that we love to do in the outdoors away from civilization.

Of course not. We come for the skiing, the snowboarding, the hiking-camping-fishing-everything

else that we love to do in the outdoors away from civilization.

Still, environmental psychologist Bree Kessler finds that quizzical. Because where do we spend most of our time? In fact, where does fully half the population of the state live? Right here in Anchorage.

As a longtime city dweller, Kessler arrived curious to explore the urban depths of Alaska's most populated city -- its parks, plazas, walkways, cafes, street life and character. Maybe you won't be surprised to hear she's been disappointed.

Puzzled would be her word for it. At almost every turn, she sees issues all cities with sizable populations face: a flood of immigrants and refugees, homelessness, a need for public transit, the quest for a walkable city and people-friendly open spaces, arts and culture venues, neighborhoods with close-by commercial benefits like small groceries or coffee shops.

Yes, some of these elements do exist in Anchorage, but few would argue all are thriving or well-cultivated and managed. Still she persists.

"Have you been to the Bear Tooth?" she asks with a touch of exasperation. "Clearly, people here want what cities have."

Convinced she can surface a closet urban tribe in Anchorage, this UAA public health

professor is throwing her own conference, in conjunction with the Center for Community

Engagement and Learning, to draw them from the woodwork. The half-day event starts

at 8:30 a.m. Friday, March 29 in the ground floor Den of the UAA Student Union building.

The conference is free and open to the public; campus parking is always free on Fridays.

"Urban in Alaska" will field three panels and invite audience discussion on each one:

- Architecture, Public Space and Urban Design

- Health, Education and Food

- Labor, Migration and Refugees

The panelists and their specific topics are posted on the Facebook "Urban in Alaska" conference invite.

The academic and professional experts are all lined up. What Kessler wants now is to reach out to the community, city dwellers who may or may not identify with urban life, to hear their take on these topics.

Kessler arrived in Anchorage with Bush experience and a rich academic background.

Her research took her to small villages in the Honduras and India. Her partner is

a ranger in Gates of the Arctic National Park, and Kessler has spent valuable time

on writing projects while living in its gateway, Bettles. But she misses urban life.

Kessler arrived in Anchorage with Bush experience and a rich academic background.

Her research took her to small villages in the Honduras and India. Her partner is

a ranger in Gates of the Arctic National Park, and Kessler has spent valuable time

on writing projects while living in its gateway, Bettles. But she misses urban life.

Before Alaska, Kessler spent a good chunk of time grounding herself in human behavior

in various environments. She earned three master degrees from the University of Michigan

in science, public health and social work and is currently completing a doctorate

in environmental psychology from the Graduate Center of the City University of New

York. While there, she consulted for the Project for Public Spaces, a nonprofit dedicated to helping people build and sustain public spaces that support

community.

This semester, she's teaching an Honors College class on urban space, based around

the 1980s book "The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces" by urbanist and journalist

William Whyte. Many people may recognize his most popular book, "The Organization

Man."

But when Whyte worked with the New York City Planning Department in the late 1960s, he engaged deeply with the city, using direct observation to record behavior in urban settings. With notebooks and still and movie cameras, Whyte and research assistants documented urban life in objective and measureable ways. This eventually evolved into the "Street Life Project" and became the basis of Whyte's writing on cities. Because of the rigor of his observations, the work's value continues today, often contradicting conventional wisdom about the way cities actually work.

Kessler is having her students do the same sort of observations in Anchorage, and they are discovering a city they didn't know. One small example: Students riding city buses discovered a flood of hotel workers, mostly women from Thailand, leaving the city center each evening bound for their homes in Anchorage's southern and eastern neighborhoods. "These populations are invisible," Kessler said, unless you look as closely as Whyte did.

One goal for the conference is to take all the submitted academic papers and edit them into a teaching text for her fall class on urban space. But she wants the conference to be practical, too. She hopes ideas will surface directly from the community to guide architects, planners, interior and landscape designers to help make Anchorage's urban space nicer for people to be in.

She'd like to engage Anchorage residents in their personal "mental map" of the town: If this were your final day here, where would your last walk be? She plans a grassroots website for gathering the data, called "MapmyAnchorage.com." Realizing the size of Anchorage's immigrant communities and its many relocated rural residents, she'd like to especially connect with them; they see and use the city differently than many.

Kessler remains convinced Anchorage has urbanites. "You know what I think?" she says, "Maybe, in Anchorage, it's a secret shame to admit you like the urban."

What do you think? Come to the conference and tell her.

NOTE: A version of this story ran in the Anchorage Daily News on Sunday, March 24, 2013.

"Spring 2013: Professor hopes to draw out the urban side of Anchorage" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Spring 2013: Professor hopes to draw out the urban side of Anchorage" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.