Throwing out 'cookbook science'

by Kathleen McCoy |

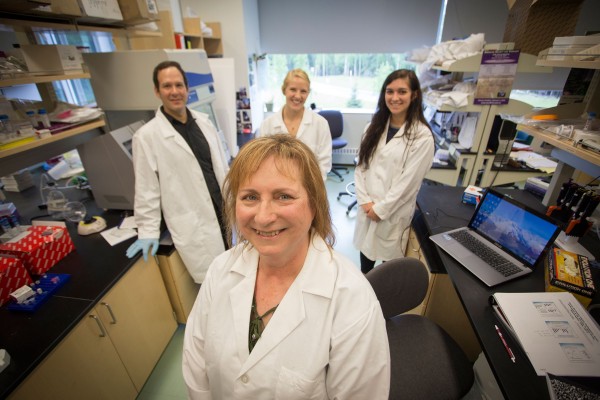

Debbra Brewer is working for the summer in UAA virologist Eric Bortz's lab. Bortz and undergraduate researchers are behind her. (Photo by Ted Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage)

Mention K-12 education these days and folks start wringing their hands with concern.

Worry mantras run the gamut:

- Kids aren't ready for college or work;

- We spend too much money on education;

- Our kids trail many in math and science;

- Schools, and their teachers, are boring (That one comes from the kids).

So it's a huge, discouraging problem. But like so many knots in life, if you scratch around a bit, you find people working toward solutions-one teacher, one classroom, one kid at a time. It's heartening.

Consider Debbra Brewer's contribution. Next year marks her 20th year teaching at Lumen Christi High School in Anchorage. It's small, with about 90 students. As one of three science teachers for grades 7-12, Brewer sees them move through chemistry, biology and forensics.

A year ago, she won a competitive grant from the Murdock Charitable Trust that paid her to work two consecutive summers in a lab of her choice at UAA. It's called "Partners in Science." She's in the middle of her second eight weeks now.

And get this: She's doing bench science right alongside a UAA professor of virology, Eric Bortz, and his team of graduate and undergraduate researchers.

Global network

Bortz is part of a global influenza-fighting network called the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance, or CEIRS.

The National Institutes for Health (NIH), which funds the influenza work at CIERS, is very interested in a cure for HIV. To that end, the agency supports the University of Alaska's INBRE (IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence) program, aimed at increasing the biomedical research capacity in Alaska. INBRE and Murdock are both supporting the HIV and cancer work in Bortz's lab.

Cellular pathways

Bortz and his crew, including Brewer, are studying pathways in human liver, lung, breast and pancreatic cells. They hope to discover precisely which signals these cells use to enlist the body's immune system for battle against infection. He'd really like to figure out if these antiviral defense soldiers can be similarly dispatched against cancer tumors and latent HIV infections no longer visible in the body.

People with HIV infection have to take drugs for the rest of their lives. If they don't, the infection reactivates, even after blood tests have revealed no present virus. That's because HIV also creates a latent reservoir of the virus within the body. Stop the medication cocktail, and HIV roars back.

Of course, you could use powerful drugs to beat it down, again. But what if the immune system did the work for you? The beauty of that, says Bortz, is the immune system's specialized efficiency.

So Bortz's tack is to purposely reactivate the HIV virus in a body primed to fight it. Experimental models in the lab have worked.

"This might be a great first step before engaging the body's immune system," Bortz said. "Because when the immune system activates, it lets the whole immune system know where the virus is. So finding the reservoir then becomes the immune system's problem. And it's really good at that."

Going after cancer tumors

Perhaps those same immune system soldiers could battle cancer, and that's where Brewer comes in. She's studying similar pathways in a leukemia cell line, using various chemotherapies.

"If we can activate antiviral defenses in tumor cells," Bortz says, "we can fool the immune system into thinking the tumor cells are infected with the virus. And the immune system will have an antiviral response. In reality, it'd be killing the tumor cells."

Debbra Brewer, a sicnece teacher at Lumen Christi High School, won a Murdock "Partners in Science" grant to work in a UAA virology lab. (Photo by Ted Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage)

This line of inquiry is fascinating for Brewer, a cancer survivor. She studied biology and chemistry at Fort Lewis College in Colorado and eventually got her teaching credentials years later at APU.

"The first thing I bring back to the classroom is renewed enthusiasm," she said. But the benefits go beyond refreshing Brewer's science background; they affect her teaching. Working in a UAA lab has also given her access to undergraduates who can describe to her what they wish they had gotten out of high school science. She's taken their advice and her lab experience to create open-ended assignments for science students back at Lumen Christi.

"I've never been a fan of cookbook science," says Brewer. "My students at this point are smart enough to go online and look up the answer. So why am I wasting class time on it?"

Hands-on science

Instead, she says, students need more open-ended discovery opportunities in science. "And they need time to 'fail.' I put that in quotes because it's not a bad thing. They need time to be in control of the experiment, and if it fails, have time to do it again. In science, mistakes are called data."

This kind of interaction is exactly what the Murdock grant hopes to inspire. As the grant website explains, "The purpose ... is to bring the knowledge from the research lab back into the high school science classroom, promoting hands-on science education."

Another incentive: After two summers in a university lab, the high school teachers have a shot at outfitting their school lab with up to $7,500 in new equipment, funded by Murdock.

The whole experience has been inspiring for Brewer. "What I am doing is part of the big picture. Maybe someday, down the line, my little piece may make a difference."

A version of this story by Kathleen McCoy appeared in the Alaska Dispatch News on Sunday, June 21, 2015.

"Throwing out 'cookbook science'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Throwing out 'cookbook science'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.