Education grad named Alaska Teacher of the Year

by joey |

Ben Walker '06, a seventh grade science teacher at Romig Middle School, is Alaska's 2018 Teacher of the Year. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

Meet Ben Walker, your 2018 Alaska Teacher of the Year.

In October, Walker received the recognition at a surprise all-school ceremony in the gym of Romig Middle School, where he's taught science to Anchorage seventh graders for the past 12 years.

This isn't the first major recognition for Walker. He was one of two Alaskans recognized with a Presidential Award for Excellence in Math and Science Teaching in 2013, the highest recognition a K-12 math or science teacher can receive.

Originally from Ketchikan, Walker moved to Anchorage in high school and graduated from Whitman College with a degree in biology. After a decade in the science field, he enrolled at University of Alaska Anchorage and earned a Master of Arts in teaching in 2006, alongside his wife Catherine Walker. (Catherine currently teaches at Dimond High School and received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Math and Science Teaching in 2015.)

A congratulatory letter from Sen. Lisa Murkowski, a former Romig student, hangs in Walker's classroom. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

Despite the career switch, Walker remains committed to science, especially the value of teaching science in his home state.

"If they want to live in Alaska, they need science literacy," he said of his students. The industries that shape the state - like oil, mining and aviation - rely on science and engineering, and he frequently invites guest speakers to share their careers with students. "I've never asked someone to come in and they said no," he said. "They're always more than willing to come in and give up a class period. Always."

Throughout his career, Walker has recognized successful education involves three things: hands, minds and hearts.

Hands-on teaching is obvious, whether it's growing plants in science class or role-playing history in social studies. But it must engage the mind, too, otherwise it's just entertainment. Likewise, "you have to have some sort of emotional attachment," he said, like the joy of discovery or the pride of achievement.

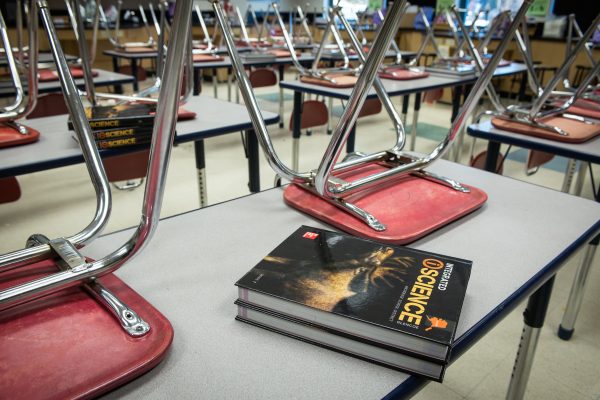

(Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

His classroom wall decorations - inspiring, educational, goofy - mirror his teaching style. There's a Dall sheep in Hawaiian leis in the corner, and animal posters with added speech bubbles telling kids to stop looking at the walls and pay attention. Collaborative lab tables border the room, with rows of desks in the center.

"You try to make things fun," he said of the environment. "We try to have a good time while also getting things done."

Kids are visibly upbeat as they tap away on Chromebooks, designing projects off a basic prompt. Choice, creativity and control are necessary to keep students invested, Walker added.

"We have too many kids who don't like school. That's a problem," he said. "You can't really succeed in school if you don't enjoy learning."

Walker unmistakably loves science and education, and his enthusiasm sets the tone for his students.

"I really enjoy the creativity of it," he said of his career. "I really enjoy the fact that every day is different. Every kid is different. Every kid is different every day."

Teacher advocate of the year

2018 will be a busy year. The award recipients from each state, territory and district will meet with Department of Education staff in D.C., tour the Googleplex in Mountain View, California, visit U.S. Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama, and even attend an on-field recognition at the College Football Championship in Atlanta.

Back in Alaska, he'll be in direct contact with the commissioner of education throughout the year, giving him a platform to address issues on behalf of the state's 7,800 educators. That number includes his wife Catherine, who previously taught in the next-door science classroom at Romig, and formerly included his mother, who once taught in the very same classroom Walker now uses.

One of his main concerns in statewide education is diversity, he said, "both on paper and when we actually implement things."

He wants the state to support education equitably in all corners of the state, not just the cities. In his eyes, students in high-population districts receive a greater individual investment, partly because rural districts spend money recruiting teachers from Outside. That short-term strategy is a common concern, and a conversation Walker hopes to continue with the commissioner this year. "I'd like someway to address that," he said.

He has a message for teachers, too: speak up at the state level. "When most of us write our legislators, we always say 'I live in your neighborhood,' when we should be saying, 'I've been teaching for 12 years, I've had this many students, this is my professional opinion," he noted. In most careers, he said, the public respects the opinions of people with experience in their field. Public discussions, though, often overlook the advice of experienced educators. Teachers' opinions are viewed as personally motivated, and Walker hopes to change that.

"I think we need to insert ourselves more as professionals," he said.

Though he's happy to receive the Teacher of the Year honor, he knows hundreds of qualified colleagues. That's why Walker takes his role as education spokesman for the year seriously.

"It's not like the World Series where there's a clear concise path to get here," he said. "This is about all teachers."

(Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

"Education grad named Alaska Teacher of the Year" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Education grad named Alaska Teacher of the Year" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.