Adventures of a 'salmon geologist'

by J. Besl |

I AM UAA: Molly McCarthy, biology graduate student (Photo by Philip Hall/University of Alaska Anchorage)

"I'm pretty sure I was predisposed to be a fish person since before I was born," said Molly McCarthy, a biology graduate student. Her family owns a small one-acre lakeside plot in northern New Hampshire, where they would spend weeks each summer fishing and camping in a stretch of American forest where cell service still has yet to reach.

These family trips are where her love of fish originated. "My dad used to tie salmon onto a rope and me and my sister would walk them like dogs on the beaches," she recalled. "There are endless videos of us doing that."

A colleague takes core samples from Upper Russian Lake on Molly's first trip to her research site. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

In fact, it was her parents who pushed her toward biology in college. She originally considered parlaying her math skills into accounting, but her dad urged her to reconsider. Instead of number crunching as an accountant, she ended up at Unity College in Maine carrying tranquilizers into bear dens on field trips and borrowing a professor's gear to go electro-fishing on weekends.

"It's funny, I started doing wildlife biology...but I decided I really liked my fisheries classes better, and I did not want to have to take soil science," she said. "I was so opposed to taking soil science that I switched my major."

In the summer months, Molly, her research assistant Nicole and a friend hiked 60 pounds of research gear to Upper Russian Lake-an 18-mile round trip. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

A few months later after graduating with a degree in aquaculture and fisheries, she was off to Alaska to start her master's at UAA where she works, of all things, in soil science.

"My project has to do with salmon, but I don't have to touch any fish or even see fish," she said. "I'm actually kind of a salmon geologist with this project, which is horrifying and hilarious at the same time because I was so opposed to soil science."

Rather than work with fish directly, Molly is instead taking sediment samples from lakebeds to determine historic fish populations. And it's been a muddy, messy, windy adventure.

Arriving on Afognak

Molly is smitten with salmon. She interned as a salmon biologist on the east coast, but realized the declining Atlantic salmon populations would decline her career prospects as well. So she set her sights on Alaska, contacted a fish culturist and requested to work at a hatchery on Afognak Island for two weeks.

Molly's first trip to Alaska coincided with the mid-August salmon run on Afognak. "All the salmon were coming back to the hatchery. It was so insane, there were grizzly bears running around," she recalled. After two blissful weeks immersed in both aquaculture and Alaska culture, she returned to the East Coast for her senior year knowing full well where she'd be moving after school.

She graduated in May 2013 from University of Rhode Island, accepted her placement at UAA in June and moved to Anchorage that August.

A summer snapshot from Molly's salmon research at Upper Russian Lake. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

Cheeseburger isotopes

The Russian River as seen from a floatplane en route to Molly's research site. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

Since arriving, she's spent the bulk of her fieldwork in the upper reaches of the Kenai Mountains at Upper Russian Lake. As a self-described "salmon geologist," Molly is busy taking core samples-basically sinking a giant straw into the lakebed and removing layers of sediment. These cores are windows to the past, with each new layer of sediment affected by the size of the fish population. Salmon rear in Upper Russian Lake and eventually head downriver to the ocean, where they are exposed to a completely new nutrient system. There are two forms of nitrogen in the oceanic food chain-when salmon feast on plankton, they take in those nitrogen isotopes. The heavier isotope lingers in their little salmon systems and travels with them when they return to freshwater to spawn.

"The lighter isotope just gets metabolized through the systems of the phytoplankton but the heavier isotope gets retained. It's like eating cheeseburgers and getting fat from them," Molly explained.

When salmon die after spawning, they deposit those heavier "cheeseburger" nitrogen isotopes on the lake bed, and each season adds another layer of isotopes. Taking a core sample of these layers shows how much marine nitrogen exists from certain time periods, which in turn indicates the size of the salmon population.

One of Molly's Belgian colleagues coring on Upper Russian Lake in winter. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

Winter winds and summer storms

Molly first visited the lake in winter accompanied by a Belgian research trio with a similar project. They loaded their equipment into a floatplane and landed on the icy sheen of the lake for the first of Molly's many research adventures.

Every season offers its challenges for research at Upper Russian Lake, but winter at least provides the stability of the ice. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

"They only had a day to help me, so we just ran across the lake and were like Core! Core! Core!," she laughed. "The problem is the cores can't freeze, so we had to run them back to this backcountry cabin." The high winds swept snow off the surface, leaving a flat expanse of black ice. Molly-precious research in hand-skittered and sprinted back and forth with the samples throughout the day.

"It was an experience, that's for sure," she said.

Winter, though, is the easier season to sample, as ice provides stability and consistency. When Molly returned in the summer, she described the weather as "rainy, windy, horrible." With a floatplane scheduled to pick her up the next day, she shipped out on the frothing lake in a boat with broken oarlocks. "It was so windy that, per one row, you get knocked back," she recalled. "It took me three and half hours to get where I needed to core." Once at the site, she dropped four rocks as anchors, lowered equipment to the lakebed 80 feet below, then leaned into the frigid waters to cap the cores as her assistant pulled each from the water. Just another day as a biologist.

A few core samples-with visible stratigraphy-wait for analysis in the lab. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

She's since returned two more times, but without the luxury of floatplanes. Instead, she hiked the 18-mile round-trip trail to Upper Russian Lake schlepping 60 pounds of equipment along with her research assistant-Nicole Warner of UAF-and a friend who she duped into joining-"I convinced a friend to go on a 'short hike,'" she smiled.

Molly is now in the lab working exclusively on her thesis, looking for biological materials she can use to carbon-date the densely packed sediment (a few inches of a core sample could contain nitrogen records from several hundred years).

"The ultimate goal is to reconstruct salmon abundance in these lakes over the past thousand years," explained her advisor, Dr. Dan Rinella. Once she knows historic salmon numbers, Molly can correlate her data to outside research on climate change and determine whether-and to what degree-climate affects salmon populations.

Statewide outreach

Aside from working on Upper Russian Lake, Molly is also coring on Skilak Lake. Due to the variable weather conditions (no ice last winter, crazy winds this summer), she hasn't made it out on the lake yet, but her Belgian colleagues provided a Skilak core for her research. Reconstructing salmon abundance in Upper Russian Lake, a clearwater lake, and Skilak Lake, a glacial lake, will provide insights on how salmon populations in two distinct rearing environments change over time, and whether the populations change in sync with each other.

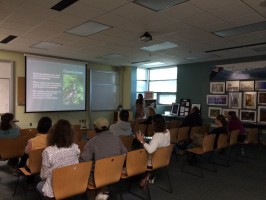

Molly's research grant focuses on outreach, and she's held a dozen forums to share her findings with the public. (Photo courtesy of Molly McCarthy)

Confused? In addition to research, Molly's research grant also focuses on education and outreach, which she's happy to provide. Scientific research is often so dense even biologists like herself can't understand it, so Molly's made a point to share her work with the public. "I like to do public seminars to make my research understandable," she explained. "I think that is something that's really important."

In addition to her dozen public seminars so far, she's led discovery labs at Kachemak Bay Research Reserve, educated kids on the salmon life cycle at the Kenai Watershed Forum and assisted in programming at UAA's ANSEP program.

It's been an adventurous research project in the field, but the outreach has been just as rewarding. For someone who can readily relate nitrogen isotopes to cheeseburgers, she certainly could make a career in outreach. Wherever she ends up, and whatever the weather, her outlook will still remain sunny.

"If I could get a biologist job at Fish and Game, awesome. If I can't and am doing education outreach somewhere, awesome," she laughed.

Written by J. Besl, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Adventures of a 'salmon geologist'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Adventures of a 'salmon geologist'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.