Professor helps Cup'ik children discover a passion for books

by Tracy Kalytiak |

It's well-known that children whose parents read to them from an early age are more likely to thrive later when they begin attending school.

UAA Professor Kathryn Ohle recently won the 2015 Selkregg Award for her work to grow early literacy and preserve the Cup'ik language in the Chevak area. (Photo by Philip Hall/University of Alaska Anchorage)

But what if a parent is Cup'ik and doesn't know English well? What if that parent can't find books written in the language the family uses at home, making it difficult not only to read to a child but for that child to see (and later explore) books written in his or her native language?

UAA Professor Kathryn Ohle recently won the Selkregg Award for her efforts to find a way to help Alaska Native children hear someone reading to them in their native tongue; preserve an Alaska Native language; and open access to reading materials in the children's native languages-both in school and within their homes.

This is important, Ohle said in her Selkregg application, given that the number of books in the child's home and the frequency with which the child reads for fun is also related to higher test scores, as reported by the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

A scarcity of books in a child's native language also sends a powerful negative message.

"When students do not see a plethora of materials in their own language, one of the unintended consequences is that students do not see that others value the language," Ohle said. "Making sure materials are available in those languages is of utmost importance for both literacy development and preservation of culture."

Helping kids discover reading

Ohle formed a partnership with Unite for Literacy, a community organization working toward amassing a free digital library with books that celebrate the languages and cultures of all children while cultivating a lifelong love of reading.

The library contains fluent native-speaker narrations of 130 nonfiction children's books both in English and in languages that include Arabic, Burmese, Cherokee, Chinese, Farsi, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Karen, Karenni, Kekchi, Korean, Mopan, Navajo, Polish, Portuguese, Q'anjob'al, Russian, Setswana, Slovak, Somali, Spanish, Tagalog, Turkish, Vietnamese and, now, Cup'ik.

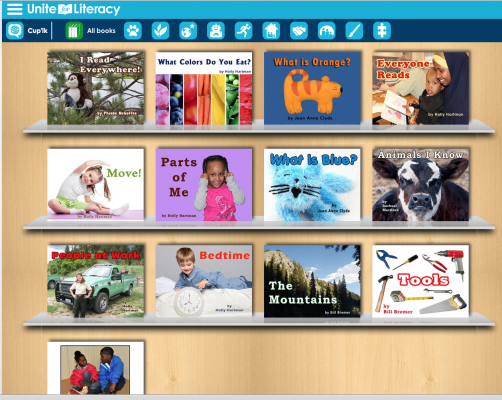

Unite for Literacy now features 13 books translated into Cup'ik by Alaska Native speakers of the language from Chevak. (Screenshot from Unite for Literacy website)

Thirteen books in the Unite for Literacy library have narrations in Cup'ik, thanks to Ohle, who is in the process of growing that online Cup'ik book selection and plans to use the $5,000 Selkregg Award to produce hardcover children's books in Cup'ik, Iñupiat and another Alaska Native language.

In 1988, the Alaska School Board identified 39 barriers Alaska Native students encounter while going to school, difficulties that create inner conflict for students and extra challenges as they attend school and balance other parts of their lives, according to the Guidebook for Integrating Cup'ik Culture and Curriculum.

The barriers, according to the Guidebook, are lack of self-esteem, lack of cultural understanding by educators, lack of appropriate curriculum, lack of opportunity to develop language skills and the school not reflecting the culture of the community.

People living in the Chevak area speak Cup'ik (CHU'pik), a Hooper Bay-Chevak subdialect of Yup'ik distinguished from Yup'ik by the change of "y" sounds into "ch" sounds, represented by the letter "c" and some words that are completely different from Yup'ik words. The language has an 18-letter alphabet and incorporates a number of Russian "loanwords"-words borrowed from Russian and incorporated into Cup'ik without translation.

Cup'ik children attend school in a single-site school district, the Kashunmiut School District, where English and Cup'ik bilingual education is offered.

Revitalizing a threatened language

Ohle, who is originally from Midland, Mich., earned her bachelor's degree in family community services from Michigan State University and then received a master of arts in teaching degree in child development from Tufts University. She then taught kindergarten for three years and third grade for two years before earning her Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This is Ohle's second year in Alaska. Last year, one of her Alaska Native students invited her to go up to the Inuit Circumpolar Council's Education Symposium in Nome.

"I was lucky because my dean provided funds for me to go to Nome and attend that," Ohle said. "When I was sitting there, I was hearing about all of the different educational issues Yup'ik and Iñupiaq populations are facing. One of the issues was language revitalization and a second was people talking about trying to teach Iñupiaq but not having any resources to do so-'What do I use when I'm trying to teach these high-schoolers? I don't have the books or any materials to use.' That kind of stuck with me as being an issue."

Ohle had specialized in early literacy-it was one of her research areas. "I thought, OK, I'm hearing about all these different issues," she said. "This is one that maybe I could have an impact on."

'Snugglyaq'

That summer, Ohle traveled to Chevak to teach a class about family-community partnerships. "A couple of my assignments involved translations," she said. "That's part of community engagement is making sure families and schools are communicating in ways that they can understand each other."

Seven students in her group were from Chevak and two were from Anchorage. All seven that were in Chevak are bilingual in both Cup'ik and English.

"One of the assignments was to go to this free digital website, library, and pick a book, translate it and then create a lesson plan that would go with it," she said. "All of them chose that option. So they had to pick four out of six options. When I was there, I said, 'Well, you already did the translation of the book; do you want to narrate it? Do you want to see if we can get Cup'ik on this website? And they did!"

After they had six hours of class with Ohle, the students went and fed their families before coming back to the school to sit for three hours in the teachers' lounge.

"They had their translated books, they were double-checking it with the Yup'ik dictionary and then they were sitting there practicing, reciting them, and then I recorded them," Ohle said. "So during that one evening, we got 13 books recorded."

Ohle talked to an official with Unite for Literacy; he helped splice and edit the recordings, and had them uploaded within a month.

Encouraged, Ohle applied for a community engagement grant through the UAA Center for Community Engagement & Learning and received a small grant enabling her to increase the number of Cup'ik-language books from 13 to 50 books.

Two students in UAA's College of Education who are also working as teacher assistants in Chevak-Susie Friday-Tall and Cora Charles, aided by Darlene Ulroan and Marnita Nash-translated the 13 Cup'ik books currently in the Unite for Literacy library. "With that community engagement grant, I'm paying them to translate more books to add to that library," Ohle said.

"Everyone Likes to Read," "Eating the Rainbow," "Bedtime" and "Tools" are a few of the books with recorded Cup'ik translations. (The written part of the book is in English).

"The women got such a kick out of doing it because there are some words they just don't have in Cup'ik," Ohle said. "For example, the bedtime one, one of the words was, 'I get my snuggly.' We really laughed about how do you translate 'snuggly' into Cup'ik? I think they just add an 'aq' to it-'Snugglyaq.'"

Hurdling challenges

The recorded books can help even if a child has teachers who come from the Lower 48 and don't know the Cup'ik language.

"But they could still be promoting this early literacy by putting their students on iPads or computers," she said. "It levels it out a little bit in terms of how we look at language. It's giving the Cup'ik the same level of value and importance as English. You can listen to these books in both languages."

Ohle is awaiting the translations of more books for the website.

"All of these women who are translating are teaching and have families and are living subsistence lifestyles," Ohle said. "This is an add-on thing for them. I understand all of the other things happen first. When it comes down to it, if they need to butcher a seal or translate a book, they're going to choose butchering a seal and I appreciate that and understand that."

Unite for Literacy doesn't offer books in written Cup'ik, yet.

"They're really focused on oral language, that is the intent," Ohle said. "A lot of these languages are oral in nature. The orthography is a recent creation, not necessarily something all of these groups initiated themselves. You had Westerners coming in, saying we need an orthography so your language lasts, which some people accept.

The Selkregg grant will address this issue, as well as pay for translations of the online books into Iñupiat and additional Alaska Native languages-while Ohle started in Chevak, she says she wants to reach out to other communities, other language groups, as well. Ohle says she began working with Iñupiaq translators in December.

It will also be used to buy hard-copy books and transport Ohle to Chevak so she can observe students using the books and use that research to make a stronger case for the benefits of the books and make it possible to get bigger grants. "There has to be some kind of tangible benefit besides, 'This was a nice idea,'" she said.

About a quarter of Ohle's Selkregg budget is going to be spent transforming these books into 250 hard-copy books.

"I'm going to have the English version but first I'm going to have the Cup'ik version written," she said. "That kind of gets rid of some of the problem. They can still listen to it here but when they have a hard-copy book they'll see the English and the Cup'ik translation. I'm doing that this summer."

There will be a few challenges ahead, Ohle said.

"It's funny...the word for 'pink' is 14 letters long in Cup'ik," she said. "I have to think about how I'm going to rearrange it on the page because that changes things."

Ohle says she is copying and re-creating all of the books using an online publishing tool, Blurb.com.

"Unite for Literacy is all digital but I am going to make them physical," she said.

'Targeting this little narrow piece'

The 13 books that are online now are very easy to read, relevant for young children and consistent with the other free books Unite for Literacy offers, Ohle said.

"I will get criticism-'Those books show kids reading in trees and we don't have trees on the tundra,' or, 'That's not a Native folktale,'" she said.

Ohle says she understands that and thinks it's a valid criticism.

"But we use books for a lot of different purposes," she said. "There are patterned[-language] books, decodable books, books for increasing vocabulary, books that promote historical context and books that promote Native traditions. There's just a lot of different categories of books and I'm only trying to target this little narrow piece that fosters early literacy skills. It's exciting to go to a drop-down menu and see Cup'ik listed. That's really cool."

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement.

"Professor helps Cup'ik children discover a passion for books" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Professor helps Cup'ik children discover a passion for books" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.