Oreos and obesity: Probing the phenomenon of impulse

by Tracy Kalytiak |

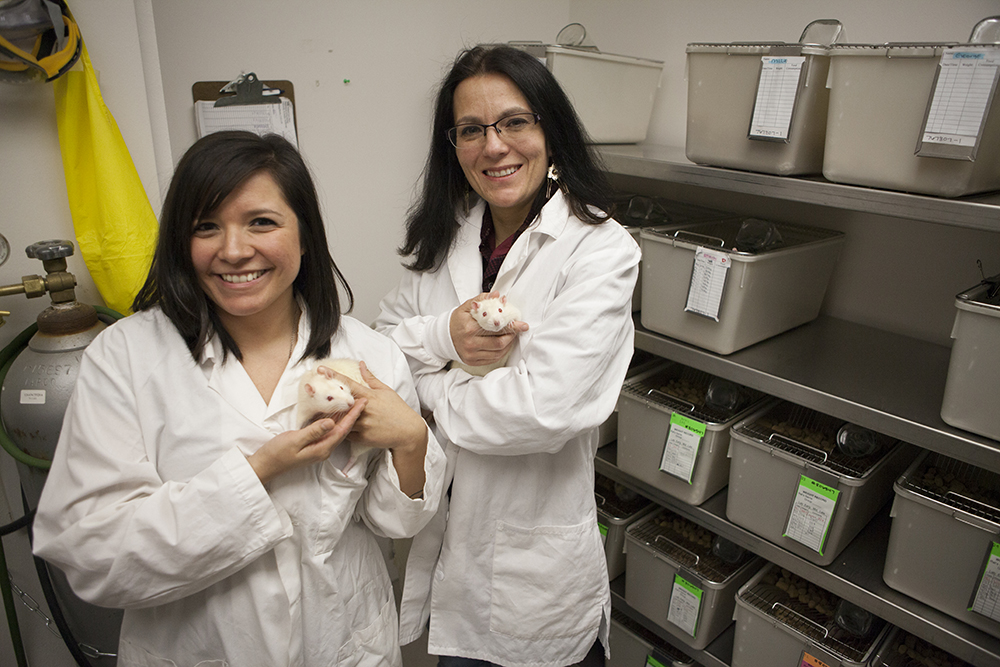

Amanda Cano, left, and Dr. Gwen Lupfer commune with subjects in Cano's research into impulsivity, obesity and binge-eating. The Alaska Heart Institute funded the research. (Photo by Philip Hall/UAA)

If you were to eat as many Double Stuf Oreos as you could, in five binges over a period of four weeks, would you be more likely to balloon into obesity than someone who simply considers Oreos a calm, steady mainstay of their daily diet?

What role does impulse play in predicting binge-eating and obesity, and are there any other psychological links between the two?

A UAA psychology student, Amanda Cano-with the guidance of her professors, Dr. Gwen Lupfer and Dr. Eric Murphy, and the help of 12 albino lab rats-is probing the role impulsivity plays in overeating. Her work is taking place with the help of the Alaska Heart Institute's Summer Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) in Health and Wellness Award and the UAA Honors College. Cano and three other students have been working individually with faculty mentors on health-related research projects.

"In humans, both binge-eating and obesity have been related to being impulsive, to having a preference for short-term small consequences instead of long-term, bigger-but-delayed consequences," Lupfer said. "So we wondered in rats how much would impulsivity relate to their binge-eating, how much would it relate to their diet-induced obesity proneness."

Reaping a sweet reward

Measuring impulsivity is by far the hardest and longest part of Cano's experiment, Lupfer said. It required computer-programming Cano did herself, building on a program Murphy devised.

Cano's experiment is divided into three segments. To examine impulsivity, Cano places a rat in a soundproof, computer-operated operant chamber-also known as a Skinner box. The chamber is fitted with retractable levers, lights and food dispenser and keeps track of what Cano's computer program records: Will the rat press one lever that instantly provides one sugar pellet, or another that dispenses five sugar pellets after a significant delay? And, how long does it take the rat to learn that being patient will reap a greater sweet reward?

A rat used in UAA psychology student Amanda Cano's research moves around inside a computer-controlled chamber that records whether it chooses to get a small treat immediately or wait longer for a bigger treat. (Photo by Philip Hall/UAA)

"Amanda adapted a choice-delay task similar to one you'd offer a child: You can have a little cookie now or, if you wait five minutes, you can have a big cookie," Lupfer said. "Amanda programmed our Skinner boxes to give [the rats] a similar choice."

While examining obesity, Cano fed the rats a steady diet of pink sugar-and-lard pellets for two weeks and weighed the rats daily. To examine binge eating, Cano provided the rats unlimited access to Double Stuf Oreos and their customary food for 24 hours every five days.

Cano's work could someday provide the underpinning for research at UAA into the ways impulsivity relates to drug abuse, gambling and even unsafe sex.

Putting rats through their paces

During one afternoon of her work, Cano gently placed one of her rats, Pinky, into something resembling a lidded metal colander and typed "420 grams" on a laptop. Then, she inserted Pinky in the soundproof chamber fitted with a peephole, vents, two levers and food dispenser, and closed the door.

On the other side of that peephole, a light flashed, the levers popped into view and Pinky quickly pressed the right lever-Click! He languidly explored, sniffing here and there, waiting. Sixty seconds passed. Then, five 45-milligram banana-flavored sugar pellets appeared on a small metal tray. Pinky immediately gobbled the reward he had patiently waited for and pressed the lever when another flash of light signaled he could choose again.

The experiment showed Pinky tended to be patient-he decided to wait for the large payout-five pellets-rather than pushing the left lever and immediately getting a small reward-one pellet. Another rat Cano worked with, Xen, proved to be the most impulsive, choosing 65.57 percent of the time to opt for the immediate one-pellet payoff.

Cano already put Pinky through the diet-induced obesity segment of the experiment that gave him two weeks of constant access to pink pellets made from a recipe using 19.5 percent lard, 3 percent soybean oil and 77.5 percent sugar.

He earned the distinction of becoming the most obese rat, packing on 21 grams overnight-a gain of nearly 5 percent of his body weight. That would compare to a 200-pound man putting on close to 10 pounds overnight, or a 120-pound woman adding nearly 6 pounds overnight.

Cano measured the rats' diet-induced obesity after giving them constant free access to a high-fat, high-sucrose food. She measured bingeing by seeing how much of an even more fattening and delicious food they ate in a short period of time.

"You might think those are things that go together, right?" Lupfer said. "The more you eat of Oreo cookies in four hours, the more you're going to eat of fattening food and the fatter you're going to get. But they seem to be different...is [Cano's] finding so far.

"The ones that binge for four hours on Oreos the most are not the ones that get the fattest when they have constant access to food," Lupfer continued. "Actually for Amanda, they've been the opposite ones."

'That's when I was just blown away'

Cano moved to Anchorage three years ago from her native El Paso, Texas, when her husband transferred here as part of his military service.

She enrolled at UAA and, earlier this year, enrolled in Psych 355, Learning and Cognition, with Lupfer and behavioral neuroscience, Psych 370, with Murphy. She earned stellar grades in both classes.

"I enjoy observing situations and I kind of like thinking outside the box and critically," Cano said. "So basically psychology was my first choice, thinking maybe I can do this. As I started learning more about what psychology was, I loved it. I wasn't sure what I wanted to do with my degree, but then I took Dr. Gwen and Dr. Murphy's classes and that's when I was just blown away."

The two professors thought Cano would be an ideal person to conduct UAA's first research into impulsivity. Cano hopes to conclude her work by the end of November. She will then include her findings in her thesis and present those findings at a conference after that.

Experimental psychology fascinates her.

"I want to learn more about the phenomenon of choice-delay," Cano said. "I just think it's so interesting how a rat knows how much more valuable one lever is than the other lever and how it continues to choose a lever, the mechanism of how they behave. I love the rats-they're like little dogs."

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement.

"Oreos and obesity: Probing the phenomenon of impulse" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Oreos and obesity: Probing the phenomenon of impulse" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.