UAA’s Robotics Club hopes to land their Mars-style rover in the Utah desert at the 2018 University Rover Challenge

by cmmyers |

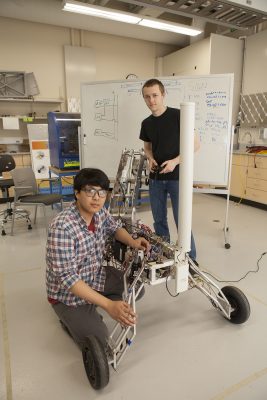

Dustin Mendoza, left, and Trevor Sprague work on their robot for the upcoming University Rover Challenge in June 2018. (Photo by Philip Hall / University of Alaska Anchorage)

In the basement of the newly remodeled Engineering & Computation Building, on the University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) campus, a dedicated group of students meets each Friday afternoon - all with the goal of creating a robot, but not just any robot. This robot, if all their hours of calculations, designs and redesigns go according to plan, in theory, could go to Mars. Or, at least to the University Rover Challenge, an annual competition held each June in Utah by the Mars Society, a nonprofit dedicated to human exploration of the red planet.

So who are these students, and why are they putting in 10 or more hours a week to build a robot on top of full class loads, studying and work ?

Meet UAA Robotics, also known as Iceberg Robotics, a club on a mission to Mars - or the Mars-like state of Utah - where the URC will take place in June 2018. UAA's robotics team was founded two years ago by Trevor Sprague, a junior in the College of Engineering's (CoEng) electrical engineering program who also serves as the current club president. Others involved in this project include Erik Williams, Grey Chalder, Heather Lindsey and Elliott Morris, as well as Dustin Mendoza, a recent graduate who is now working for Intel.

There are many more members, and involvement tends to fluctuate depending on the time of the semester. But the core founding members have remained dedicated to their mission of building a robot that could traverse the red planet's harsh conditions

"This team is pretty self-motivated," said UAA Robotics faculty advisor Matthew Kupilik, an assistant professor of electrical engineering in CoEng. "This is mostly student-driven - we give them a space and some general advice and they run with it. Their motivation is impressive and I think they have a lot of fun doing it."

Iceberg ahead

Sprague has loved all things robotics and his fascination has kept him captive all through elementary school to college. However, when he came to UAA, there wasn't quite the right club to fulfill his robotics needs - at least not yet.

"When I came here, there was a couple of clubs that I knew about, like Baja [a collegiate competition to build and race a mini off-road vehicle, sponsored by the Society of Automotive Engineers] and they're mainly mechanical design, and there's the steel bridge, which is mainly civil [engineering] and geomatics," Sprague said. "There wasn't really anything that was electrical and programming - bridging the gap between everything - so I started thinking that it would be pretty cool to do robotics again."

Sprague thought, why not start a new club - one that focused on the engineering areas that interested him. In spring 2016 he got together with a group of his friends and classmates and they started to put the wheels in motion for a new engineering club at UAA.

It took a while to get the club off and running, but in September 2016, the fledgling group found a graduate student willing to help the club get started in the right direction.

"He was really able to help structure things, organize and motivate us to work on projects," recalled Sprague. "We decided to compete in the University Rover Challenge, where we build a Mars-style rover, like the Curiosity, except on a much smaller budget."

UAA Robotics year one

In 2016, the team took the plunge and decided to enter the 2017 URC competition. They spent months designing their robot in Solidworks, a 3-D software design program, and worked closely with CoEng machinist, Corbin Rowe, to ensure their designs were feasible, manufacturable and would actually work in "real life."

Sprague said the team's rover is judged by a panel on the completion of four tasks. Their rover must be able to perform: a science experiment; an extreme retrieval - where the rover drives to retrieve an item like a rock or soil; an autonomous traversal - how well the rover's software performs on a 1 kilometer drive; and a terrain traversal - where the team sends their rover off a small cliff and over rough terrain.

Additionally, they have a weight limit of 50 kilograms, communication protocol questions the team must answer, and they are not allowed to use an internal combustion engine or a drone - because they won't work on Mars. The design, mechanics and everything else? That's up to the teams.

When the team was ready, they submitted their proposal and critical design review - which was basically an explanation of their rover and the UAA Robotics Club.

"We wrote up a written document and submitted videos - and that's where we got cut," Sprague said. "We missed it [qualifying for the competition] by two out of 140 points." It was a tough pill to swallow - especially since they got so close.

Sprague said they had some stiff competition and that about 80 teams entered the URC last year, representing countries from Asia, Europe and across the U.S. UAA Robotics was vying for a spot in the competition against some of the top universities in the country, like Cornell and Yale.

"We were just starting out and we didn't get funding until about October or November-ish," Sprague said. "So what we're doing right now is trying to learn from last year - what worked and what didn't work."

Essentially, the group is going back to the drawing board and redesigning their rover. They're ahead of the game this year - having done this once before. While most students headed into their month of winter break preparing to relax, UAA Robotics club members were in the lab, building a robot.

UAA Robotics year two

Currently, 95 teams, representing 12 countries, are committed to competing in 2018. Thirty-three of those teams are from the U.S., including Ivy League robotics clubs and public universities with well-respected science programs.

As UAA Robotics prepares for next summer's competition, Sprague said he and his team are focusing on their rover and how they can improve their design from last year.

"We've looked at what NASA's done for a little bit of inspiration and what teams have done in the past," Sprague said. "From there, we'll put together what we think will work."

Last year, the robotics club had about 10 to 15 members who consistently put in the time to build the rover for the June competition. This year, Sprague said more than 40 students came to their club meetings at the beginning of the semester.

"It was absolutely insane - we weren't ready for that kind of influx," he said, explaining that things have calmed down a bit since those initial meetings. "Right now we're down to about 20 to 25 students, and we actually have a couple of different design teams."

One team is working on the arm, while one is working on the suspension and one is handling the rover's battery design. He said dividing the project into team groups has made it a lot easier, especially for setting deadlines.

Sprague said additional team tasks include: chassis design, electronic sourcing, software programing, as well as developing a science task that URC requires each competitive rover to complete. He said they've pulled in students from math, civil engineering and mechanical engineering to have the rover dig into the ground, retrieve soil and transport it back to its base. The team will then perform experiments on the soil to see if there are signs of life and present their findings to the panel of judges.

"I've been working about 10 hours a week - up to 25 when it gets really busy," he said, joking that some people think maybe he and his fellow club members spend too much time on the rover. But he doesn't mind. "It's like a part-time job - at least that's how several of us treat it."

Kupilik said that although the club is fairly independent, he offers advice when he can and helps oversee three of the senior engineering design teams building parts of the club's rover.

"If they have questions about specific motor controllers, I can offer insight into that or general technical advice," Kupilik said.

Life after rover

There's no question that Sprague and the members of UAA Robotics is a dedicated bunch. Most of them are engineering students taking a challenging course load, spending hours studying, and on top of that have internships and part-time jobs outside of school. But, Sprague said they just make it work and that the end goal is about securing a job and obtaining a learning experience they wouldn't necessarily receive in the classroom.

"This acts as a platform to apply what we learned in class - and we're gaining real-world experience, learning how to work on a team, learning about project management - how you manage and lead a team - and how to ask for sponsorships," Sprague said. "We're learning a bunch of skills that we wouldn't learn in class."

"It's been an impressive amount of interest that they've generated - I think it's fantastic - and they're all doing it on top of their engineering degrees, which is quite a bit of work," Kupilik said.

The other big bonus? Making those community connections with local engineering firms. Sprague said the club has opened doors for him and his team members. He and several of his friends have received internships at local firms as a result of their project, and to him, that's invaluable.

"Even though this is the second year, we're seeing that there's a lot of positive outcomes," Sprague said.

Written by Catalina Myers, UAA Office of University of Advancement

"UAA’s Robotics Club hopes to land their Mars-style rover in the Utah desert at the

2018 University Rover Challenge" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"UAA’s Robotics Club hopes to land their Mars-style rover in the Utah desert at the

2018 University Rover Challenge" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.