The Ewe and Fon in West Africa and Arará in Cuba

This arts-based research project focused on four specific communities: the Ewe communities of Dzodze, Ghana; Adjodogou, Togo; and the Arará legacy rich communities of Perico and Agramonte, Cuba, Matanzas Province.

Adjodogou Drummers, image by Jill Flanders Crosby

Dzodze Drummers, image by Brian Jeffery

In West Africa, while the Ewe and the Fon are two different peoples, historians identify a shared migration trajectory from Southwestern Nigeria westward towards present day Togo and Eastern Ghana that occurred more or less at the same time. The Ewe and the Fon not only share a physical proximity to each other in West Africa, they also share a cultural heritage and common attributes of artistic and ritual expression (Daniel Avorgbedor, interview March 2, 2008; Venkatachalam 2015).

Nemesio Lázaro Madan Baró at Agramonte's San Lázaro ceremony, image by Melba Néñez Isalbe

In Cuba, the term Arará has a complex history. In general, "national descriptors" dependent on geographical locations in West Africa were applied to enslaved Africans arriving in Cuba by slave traders and owners as if they were proper ethnonyms (Brandon 1993). Thus, the broad name Arará was given to the enslaved Ewe and Fon people who arrived in Cuba from West Africa as late as the 1860s from an area known as Alladah in former Dahomey (present day Benin and parts of Togo). Arará has no historical usage in West Africa. The Arará were largely enslaved to do work at the sugar mills in Matanzas Province (Basso 1995; Daniel 2005; Fernández Martínez 2005). Enslavement was not abolished in Cuba until 1886.

Perico drummers at Arará ceremony, image by Miguel Parera

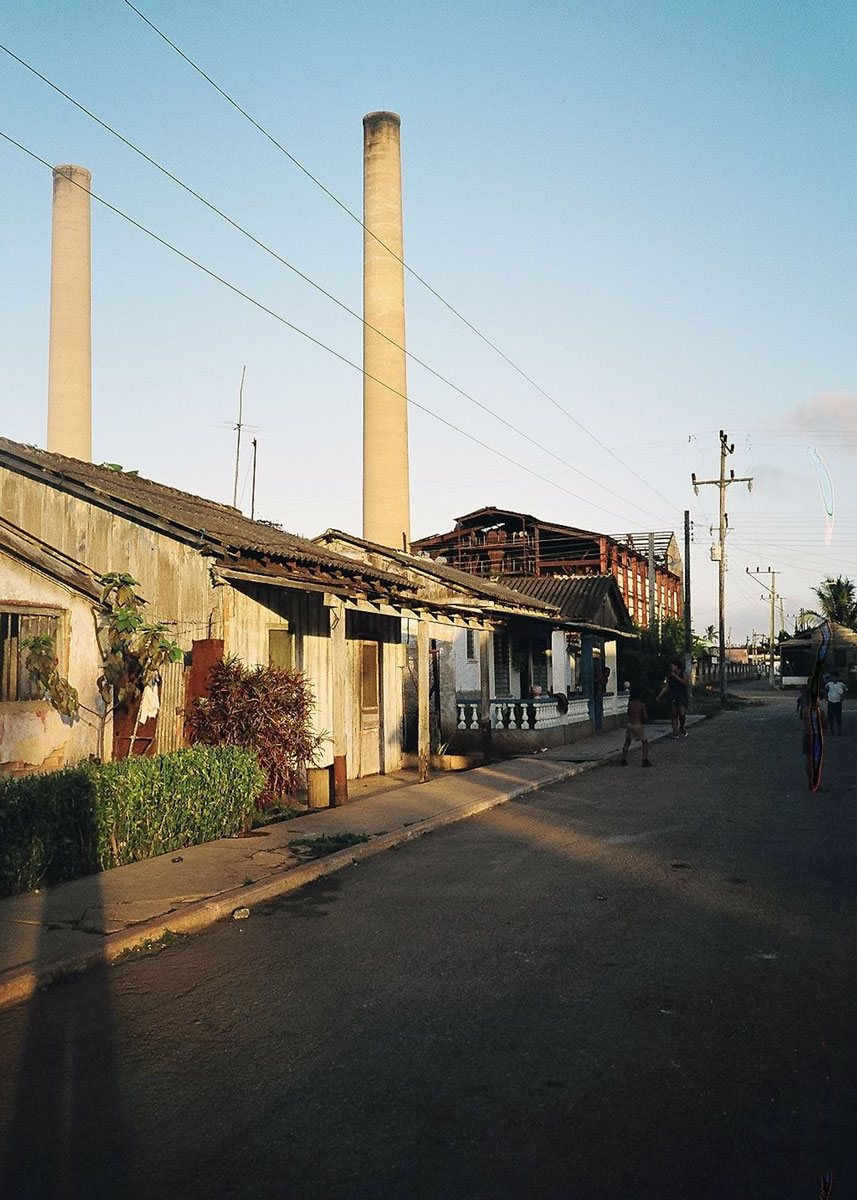

Former enslaved Africans and their descendants who eventually settled in the Perico area, were enslaved primarily at a sugar mill called España now largely abandoned and located about 5 km outside Perico. Those who settled in the Agramonte area were enslaved at a near-by sugar mill called Unión Fernández which is now in ruins.

Ruins of Unión Fernández, image by Melba Núñez Isalbe

Remants of España, image by Jill Flanders Crosby

For Ewe and Fon people brought to Cuba as enslaved Africans, their religious musical and dance expressions were their identities as a people dislocated from Africa under the weight of slavery. In Cuba, they continued their religious practices to the best of their ability.

Thus, Arará ritual practices have many shared attributes with Ewe ritual practices, primarily with those known as the Anlo-Ewe found largely in Southeastern Ghana and Southwestern Togo.

However, Arará is its own reinvention of the Ewe and Fon religious expressions as the people who practiced them endured slavery and later worked together to rebuild a sense of life in Cuba.

Dancing at the Awán Ceremony, image by Brian Jeffery

Arará as a religious expression in Cuba did not adopt a homogenous form across the Matanzas province any more than there are homogenous religious forms across the Ewe and Fon areas of West Africa. The Ewe and Fon peoples had (and still have) multiple variations of music and dance-making (Avorgbedor 2005) along with diverse deities from their respective West African communities. However, there are common and shared attributes across the breadth of the diverse Ewe and Fon music, dance, and ritual traditions.

These shared attributes and diversities met each other in multiple Cuban locations across the Matanzas province. As peoples were isolated in individual forced labor communities, Arará evolved differently at each site.

But across the breadth of Arará traditions, there are also clear shared attributes. These shared attributes include deities, often with slightly different names, and their physical representations imbued by these deities, known as fodunes or fundamentos (Daniel 2005; Fernández Martínez 2005). Shared attributes of these Cuban Arará deities and fundamentos can be discerned between the Ewe and Fon vodu deities and their imbued forms, along with aesthetic similarities in dances, rhythms, and ritual practices.

The fundamento for Sakpata in Adjodogou, Togo, image by Brian Jeffery

The Fundamento (back right) for San Lázaro in Perico Cuba, image by Jill Flanders Crosby

The Fundamento for Togbui Anyigabato (Sakpata) in Dzodze, Ghana, image by Jill Flanders Crosby

A key component to this research, in addition to the years of work in Ghana and Togo, was the extensive body of oral history interviews conducted in Perico and Agramonte primarily between 2006-2018. Interviews conducted with elders in both locations revealed rich oral histories. But through each interview runs a shared theme of transformation and retention, pride in African roots, remembered stories about relatives who were enslaved, and insistence on objects arriving "directly from" Africa.

Perico

Streets of Perico, image by Susan Matthews

In general, Perico, located in the Matanzas province, Cuba, was first a municipality that was founded as railroad lines were extended into the area from Cárdenas in the mid 1800s. In 1863, the sugar mill España was officially registered upon production of its first sugar harvest in the Perico municipality and by 1868 all the acquired plots of land of Julián de Zulueta y Amondo, owner of España, belonged to the municipality of Perico. According to residents in Perico and documents located in the Perico’s municipal museum, the first Arará settlement was registered in 1863, although the enslaved most likely arrived around 1861. The majority of the enslaved peoples who labored at España were brought from West Africa mainly from the former Kingdom of Dahomey (present day Benin and parts of Togo, West Africa).

Streets of Perico, image by Susan Matthews

Perico, as a town today, is where freed Africans from España were eventually re-settled. Evocative elder oral history stories illuminate its growth and the rise of its Arará ritual practice. Many of these stories can be found on Susan Matthews' page. These manuscripts are all based on the interviews conducted in Perico by the research team of Jill Flanders Crosby, Melba Núñez Isalbe, and Roberto Pedroso García between 2005 and 2010. Of these stories, Ma Florentina's story is perhaps the most legendary and well known.

Fundamentos at Ma Florentina's cabildo, image by Jill Flanders Crosby

According to the still circulating story in Perico, Ma Florentina was a princess in Africa before her capture. Therefore she was not only treated differently by other enslaved Africans at España and by the refinery owners, but she was allowed to bring objects from Africa to Cuba. After she was free, Ma Florentina was instrumental in starting la Sociedad Africana (The African Society House) in 1887 in Perico (Andreu Alonso 1997). According to elders, la Sociedad Africana was the heart and soul of Arará in Perico, functioning as a collective aid society and as a center of religious activities. Oral history tells the story of how early members collectively housed their individual fundamentos together under the roof of la Sociedad Africana. After the death of Ma Florentina, the various fundamentos were dispersed and went to live in houses of individual family members.

The fundamentos are still cared for and revered by the current descendants of their original owners. La Sociedad Africana is currently under the direction of Víctor “Prieto” Angarica Diago, who is grandson to Ma Florentina's goddaughter Victoria Zulueta.

At Ma Florentina's, her fundamentos, fundamentos that once belonged to other friends or godchildren, and her drums still receive annual ritual blessings by Prieto's extended family and religious leaders in Perico.

As well, Perico is well-known for the stories of Armando Zulueta who had a strong and important San Lázaro, and the annual awán still held every December 18.

Prieto Angarica Diago at Awán Ceremony, image by Brian Jeffery

Ma Florentina's ritual Arará drums in 2010, image by Brian Jeffery

Armando Zulueta (center), image by Melba Núñez Isalbe

Sociedad Africana under renovation in 2006, image by Susan Matthews

Agramonte

In Agramonte, a half an hour drive from Perico where stories of Perico Arará elders are known and shared in Agramonte and vice versa, African roots are as resonant as in Perico. The ruins of Unión Fernández, located outside of Agramonte, once housed a sugar operation. Many enslaved people who labored there eventually settled in nearby Agramonte. In December 2007, the research team all spent an afternoon in Agramonte, sitting on the porch of 93-year-old Hilario "Melao" Fernández Sosa as he narrated stories of Manuela Gose, popularly known as Ma Gose. According to oral history, she and another elder called Coso-Coso were both tricked into getting on board a slave ship and were brought to Cuba to work at Unión Fernández. After her freedom, Ma Gose continued to live at the small batey (community) of Unión de Fernández before moving to Agramonte.

Next, we went to the house in Agramonte that Ma Gose lived in and talked with Ma Gose's great-granddaughter Onelia Fernández Campos and her husband Israel Baró Oruña. When Ma Gose came to Agramonte, they told us, she brought her fundamentos and established an African Society at her house sometime in the late 1800s. Unlike Perico, all the fundamentos that arrived in Agramonte as the formerly enslaved re-located from Unión de Fernández, were not housed in Ma Gose's house. Rather the fundamentos stayed with the individuals who carried them to Agramonte. But interestingly, Israel and Onelia are adamant that Ma Gose's ritual necklaces, still located in her house, came with Ma Gose when she was transported as a slave. Israel says:

Image by Jill Flanders Crosby

She brought them from Africa, but secretly because that was forbidden … That's been talked about a lot because it was difficult to bring any object from Africa, however, she brought them. That is why this is so important here since it was so difficult to bring things from there (personal conversation, December 31, 2007).

Image by Jill Flanders Crosby

There are several evocative stories about Ma Gose. According to Agramonte ritual leader Mario José Abreu Díaz, during the dry season, Ma Gose threw water upwards, spoke in Dahomeyan language and rain began to fall on her property. One time, he told us, she was taken to jail in trance with her San Lázaro during a celebration at her house (the story of why she was taken to jail has, apparently, been forgotten):

He narrated:

They put her in jail. They took Ma Gose to the police headquarters and she was in trance with San Lázaro. They locked her in the cell and every time the guard went to sleep, she was sitting by his side, 'oh I left the lock open.' Those are the stories. 'Son take me to my house' for the celebration couldn't continue. When they were going to lock her for the third time, the lieutenant of the guard arrived … and said, 'ah what is Ma Gose doing here?' When they got here (Ma Gose's house), the two guards got possessed …They had to put away their guns and uniforms (personal conversation December 31, 2007).

Mario José Abreu Díaz in trance with San Lázaro at the Awán ceremony, image by Miguel Parera

Dzodze

Dzodze is an Anlo-Ewe community located near the southern border of Ghana and Togo. According to an informal history given to Flanders Crosby by Vincent Kofi Kodzo, Senior Executive Officer attached to the Ketu District Administrative office of nearby Denu, Togbui Adzofia migrated from Notsie with his war god known as Dey (a swarm of bees) in order to escape the Notsie leadership of Fia Agorkorli (Agokoli). Adzofia and his people eventually made their way to and founded present day Dzodze. The shrine for Dey was located in Dzodze’s Ablorme district near what would become the Dzodze market. Roughly between 1898 until his death in 1933, Togbui Ahiadzro Adzofia II granted lands for the present day Dzodze market, the police station, and the Presbyterian church in Ablorme. Located along the road that connects the community of Denu to the south and that of Ho to the north, Dzodze gradually grew as a commercially important town.

It was here that Flanders Crosby met Kpetushie Kemeh Nkegbe, a well-known priestess in Dzodze, specifically in her district of Ablorme. Everyone calls her either Amegashie (the Ewe word identifying a priest or priestess) or by her nickname Dashi. Her nickname rises from the name of one of her deities – that of Da, the Ewe word for snake, but also a vodu deity that manifests as a serpent or a snake. She was a critical interlocutor and is sister to Johnson Kemeh who was Flanders Crosby's key research collaborator during her years of fieldwork in West Africa. Her most important deity is Togbui Anyigbato, also known as Sakpata in Adjodogou, both of which share strong attributes of San Lázaro in Cuba.

Image by Brian Jeffery

Inside Dashi Kemeh Nkegbe's Togbui Anyigbato shrine, images by Brian Jeffery

Adjodogou

Flanders Crosby’s key research assistant in Togo was Bernard “Solar” Kwashie. Adjodogou was founded by Solar’s great-great grandfather Foli Gadjin. The community has remained largely in family hands to this day. Foli, before founding Adjodogou, would travel from his then present home of Aného on Togo’s south west coastline of the Bight of Benin up towards his favorite location to both farm and fish. After a time, he established a small village at his fishing and farming site where he could sleep, since it was easier than going back and forth to Aného. Others who had been coming to farm and fish also decided to stay. A small market was established at a junction along the main road between Aného and Vogan.

Adjodojou Sugar Cane Planters Association, images by Brian Jeffery

Image by Brian Jeffery

Early in the establishment of Adjodogou’s market, it became a target of attacks by thieves. According to Solar, Foli was a strong and powerful man who fought off the pillagers. From him, the town earned its name - adjo meaning attack and dogou meaning nobody can come. There are several important shrines in in Adjodogou, one for Sakpata, one for Da, and one for Yewe.

Image by Jill Flanders Crosby

Image by Jill Flanders Crosby

Image by Jill Flanders Crosby

The stories of all these communities can be found in the book Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance: Performing the Entangled Histories of Cuba and West Africa by Jill Flanders Crosby and JT Torres published 2021 by University Press of Florida. Also reference the following publications by Flanders Crosby and Torres:

Torres JT, and Jill Flanders Crosby. 2018. “Timeless Knowledge, Embodied Memory: The Performance of Stories in Ethnographic Research.” Etnofoor 30(1): 41-56.

Crosby, Jill Flanders. 2010. "The Social Memory of Arará in Cuba: Oral Histories from Perico and Agramonte." Southern Quarterly 47(4): 91-109:4.

Crosby, Jill Flanders. 2010. "Secrets Under the Skin: They Brought the Essence of Africa." In Making Caribbean Dance: Continuity and Creativity in Island Cultures Editor, Susana Sloat. University of Florida Press

References:

Andreu Alonso, Guillermo. 1997. The Arará in Cuba. Translated by Carmen González. La Habana, Cuba: Editorial José Martí 1997. Originally published as Los Ararás en Cuba (Editorial José Martí, 1992).

Avorgbedor, Daniel K. 2005. "Musical Traditions of Ewe and Related Peoples of Togo and Benin." In The Ewe of Togo and Benin, edited by Benjamin N. Lawrance, 197-214. Accra New Town, Ghana: Woeli Publishing Services.

Basso, Alessandra. 1995. Las Celebraciones Ararás in Perico y Jovellanos. Unpublished Master's Thesis, CNSEA: La Habana, Cuba.

Brandon, George. 1997. Santeria from Africa to the New World: The Dead Sell Memories. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Daniel, Yvonne. 2005. Dancing Wisdom. Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomblé. Chicago and Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Fernández Martínez, Mirta. 2005. Oralidad y Africania en Cuba. La Habana, Cuba: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Venkatachalam, Meera. 2015. Slavery, Memory, and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850-Present. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.