All about the asteroids

by joey |

Geology student Ian Minnock recently presented on asteroid porosity at the Geological Society of America conference in Baltimore. His research project, though, is completely independent of his UAA coursework. He just loves research. (Photo by Philip Hall / University of Alaska Anchorage)

When Ian Minnock brings up his research, the response is often the same. "Anytime I open with 'I'm studying asteroids,' everybody asks 'So when's the next one going to hit us?'" he sighed.

But Ian doesn't study the paths of these giant hunks of space rock that barrel through the universe. As a geology major, he studies the rocks themselves. "We know the orbital properties of 700,000 asteroids. We don't know the physical properties of 700,000. I'm just filling in that gap," he explained.

Like the protagonist in many a space-age story, Ian largely works alone. With so many diverse deltas and volcanoes and ranges and glaciers to explore in Alaska, the UAA geology department isn't necessarily focused on outer space. For an extraterrestrial enthusiast like Ian, that means a lot of self-motivated research outside of class.

Additionally, it means an independent commitment to his research. Need a powerful computer? Just build it. Want a greater connection to resources? Apply for a NASA-funded Alaska Space Grant. Ian credits his advisor Dr. Jennifer Aschoff-who he calls "an excellent advisor, the best professor ever"-for providing guidance on his self-motivated project. "She's been extremely helpful," he said.

Most students don't dive into more academics as an extracurricular but, it must be said, Ian isn't like most students. For the last year, he's been wholly focused on his research project-a statistics project on the geology of asteroids-and even traveled to Baltimore in November to share his research at a national geology conference.

An extraterrestrial extracurricular

"It really started with one class in the spring," Ian said, recounting how he started his asteroid project. He enrolled in GEO 310: Professional Practices in Geology, which focuses on everything a geologist will need to be successful in their careers (no, not fleece outerlayers and mudboots, but science writing and proposal presentation skills). The course's emphasis on research methods stayed with Ian. "I really caught on to the research side of it and wanted to do it forever," he said.

His asteroid project walks the line between geology and astronomy, but doesn't quite fit either. Planetary geologists are mostly interested in meteorites-asteroids that survive their crash course through the atmosphere and land on Earth. Astronomers, rather, focus on the origins of bodies in space-the proto-planetary dust that may become something more. Ian's interested in the mid-life era, after asteroids have formed and before they crash to the surface.

So what exactly is his project? "It's really complicated, and that's why my project is important," he said.

Okay, here goes...

Far out research

Ian's research is informed by a 2012 study from astronomer Benoit Carry that identified the densities of 287 asteroids. It sounds like a lot, but it's only 0.0004 percent of the 700,000 known asteroids and dwarf planets identified by NASA. Ian wanted to add to Carry's list.

Unlike meteorites, asteroids are still floating in space, posing a significant obstacle for geologists at ground control. So how does one determine the density of a rock hurtling light years away?

First, we need the size of the asteroid. By looking at the amount of light reflected off an asteroid, astronomers can learn the body's shape and its rotation. To determine mass, asteroids must be in cahoots with another body so astronomers can measure their gravitational pull on each other (in science terms, that's a binary orbiting system). From those two information points-an asteroid's size and sway on its neighbors-scientists can roughly determine density. Some asteroids don't have the expected pull, based on their determined density, which accounts for asteroid porosity. Ian has focused his geology research on this perceived porosity.

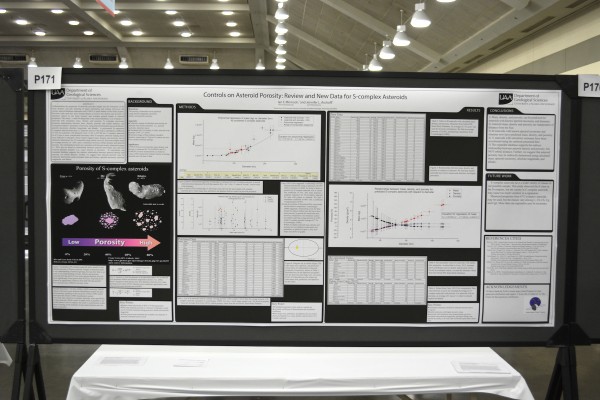

Ian turned his research into this mighty poster presentation, which he brought to the Geological Society of America conference in Baltimore earlier this month. (Photo courtesy of Ian Minnock)

To add to Carry's research, Ian consulted NASA's list of known asteroids and looked for similarities to Carry's original list. Each asteroid is listed with dozens of data points and, all told, scanning through the information meant sifting 18 million data points, enough where each regression took two days on a standard laptop ("and even then it was likely to crash several times," Ian added).

So Ian, who lives on campus, took to building a seriously powerful computer in his dorm room. The finished product will have 128 gigabytes of RAM (in comparison, most computers on campus have four to eight gigs) and will assist him as he continues plucking asteroids from the NASA list and adding them to the shorter selection of asteroids measured by porosity.

So far, Ian has added 40 asteroids to the original data set of 287, some as large as the Kenai Peninsula (still tiny on a cosmic scale). Carry's original research compared density against diameter on a linear scale, which didn't produce a great correlation. Ian instead used a polynomial scale, with data points that curve, and discovered that larger objects stopped following the trend, even though mineral composition is assumed to be pretty similar.

"You'd expect a straight line, but we don't see that. We see an exponential increase, which means that something is going on inside when asteroids reach a certain point," Ian explained.

Rocky research

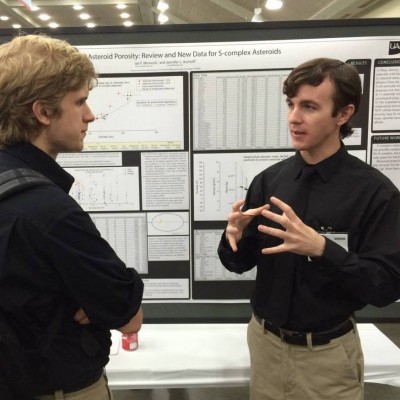

Ian's research on asteroid porosity attracted a crowd of interested Earth-focused geologists at the GSA conference in Baltimore. (Photo courtesy of Ian Minnock)

His work is still in progress-after all, there are 700,000 asteroids to parse through-but in early November, Ian spent over a week in Baltimore presenting his poster at the annual Geological Society of America conference. Again, it should be stated, Ian's research is completely independent of his geology classes at UAA-he received a travel grant from GSA to attend the conference.

Ian was the only presenter on asteroid porosity, which meant he had a steady stream of interested geologists stopping by to ask questions. The connections and conversations from the conference proved incredibly valuable. "I loved the conference," he said. "I recommend it for any science student to go out and present."

Now he's back in Anchorage with a winters-worth of independent research ahead. That's exactly what he hoped for. Ian grew up in Maui and admits that he'd probably be bumming around the beaches of Hawaii if he stayed home for college. "I came up here because it's really cold," Ian said. "I don't drive. I live on campus. I study way too much."

So far, Ian has an Alaska Space Grant and a self-motivated presentation at a national conference on his résumé... and he's still just an undergrad. His independent study has only provided further questions to explore in the future. "It's a Pandora's box," he said. "One point of research opens up an avenue of infinite ways you can continue the research."

But though he works alone, he credits his advisor for all her assistance. She's the mission control to his galaxy quest. "It's too geology for astronomy and it's too astronomy for geology," Ian said of his project. "That's why Dr. Aschoff is the greatest. She's not afraid to take a step or two out of her specialty."

Written by J. Besl, UAA Office of University Advancement

"All about the asteroids" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"All about the asteroids" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.