Research in Hawaii: 'I've never crawled around in a lava tube before...'

by Kathleen McCoy |

UAA team members standing in the opening of a lava tube on the Big Island. During winter break 2015, they surveyed for sites in the saddle between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanoes. (Photo by Gerad Smith/team member and UAF doctoral student)

Alaskans in Hawaii-happily soaking up light and sun in December and January-that's hardly news. Buy me a ticket, right?

But UAA scientists and graduate and undergraduate students, employed and paid for their scientific skills as they survey for artifacts in Hawaii-now that's something to talk about.

In these lean economic times in Alaska, the university system is working hard to reach out to the public with new inventions, ideas and skill sets. This particular project with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers happened through the Applied Environmental Research Center within the UAA Business Enterprise Institute.

BEI's role is to link Alaska businesses and entrepreneurs with the expertise and talent at the University of Alaska. AERC is one of eight centers within BEI. It places subject-area experts who can do the environmental, cultural and natural resource assessments required by public land managers. In Hawaii, that recently meant UAA students and scientists doing archaeological surveys on public lands managed by the U.S. Army Garrison, Hawaii.

Applied learning in the field

In the past two years, AERC projects have delivered more than $2.5 million in new money to the UA system, according to Douglas Causey, AERC's director. Archaeology endeavors are the anchor, delivering $1.7 million in revenue so far.

Field camp in the saddle between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, where UAA archaeologists and students surveyed for sites. Their camp is the small white tents in the middle of the image. (Photo by Gerad Smith/team member and UAF doctoral student)

That payday is welcome, but so are other important benefits, says Causey. Most of the work has been done during December semester breaks, adding a winter field work opportunity for faculty and students. Yet another plus is exposure to marketplace expectations for project delivery and completion.

"These cooperative agreements are required to operate at the speed of industry," said Christi Bell, executive director for BEI. "There is an added layer of entrepreneurial acumen incorporated that further provides our faculty and students a 'real world' experience."

Why and how Hawaii?

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Pacific Ocean Division, covers programs in Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa and the Mariana Islands. Hearing the Corps might have projects within this enormous region, AERC applied and qualified.

Members of UAA's archaeological team stand before a collapsed sinkhole over a lava tube. (Photo by Gerad Smith/team member and UAF doctoral student)

It's not that Hawaii has no archaeologists. Resident experts there are hard at work exploring environmental and cultural impacts of numerous projects advanced by private developers and land owners, as well as both state and federal agencies and governments-all to meet the state of Hawaii's historic preservation laws and regulations. Just one of those projects is a very visible railroad extension. The volume of work in Hawaii opens up opportunities for other skilled archaeologists, including UAA's experts.

So far, UAA faculty and students have conducted "archaeological pedestrian surveys" in the high elevation saddle area between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea on the Big Island, known as the Pōhakuloa Training Area. One effort covered 400 acres and the other was closer to 500 acres.

While work to date has meant walking through landscape to document evidence of human presence in upland areas of the Big Island, the team will venture closer to the coast in August for a different project on Oahu. They'll trade the uplands for jungle. Armed with machetes, they'll clear space and shovel 50-centimenter test areas and screen the dirt for artifacts.

On the ground in Hawaii

UAA Professor Diane Hanson, known for documenting human habitation in the uplands of Adak, is the principal investigator on the Hawaii projects. One of her former students, research associate and adjunct professor Margan Grover, serves as field director.

An awl, or prehistoric tool, is one item the UAA archaeological team discovered on their pedestrian surveys in Hawaii. (Photo by Rachel McKenna/UAA)

I caught up with Margan in her office in Beatrice McDonald Hall, where she was finishing a report on the team's 2016 work to date. In a lab downstairs, graduate student Ted Parsons worked on 3D images of some of their findings, which included a hearth, gourd fragments, shaped wooden tools, trail rock cairns and shelter overhangs.

Hawaii is new territory for the Alaska archaeologists. Margan wrote her master's thesis on Russian America in Sitka. She's done plenty of professional archaeology on the North Slope and in northwest Alaska, where Inupiat culture has been a focus.

"Just when I start to understand Yup'ik [culture]" she said, "now I am off to Hawaii!"

Of course, archeological field processes transfer. "I can take my skills and go anywhere and work," she said. Still, there's a learning curve between Alaska and Hawaii. One example: "I've never crawled around in a lava tube before...."

What followed for the UAA team was an intense process of learning Hawaiian prehistory, terrain and archaeology. "Most of my bookshelves are filled with Alaska books," Margan said, but another new section is growing fast. "I've been accumulating this whole library on Hawaii history and archaeology. I've read them all!"

Similar, but different

Field camp in Hawaii has parallels to field camp in Alaska. Remoteness is a common element.

On the Aleutians, for example, field teams are often dropped off by boat. In Hawaii, it was a helicopter, including water resupply every few days. "Just like in Alaska," Margan said, "no showers."

Lava tubes are a type of lava cave formed when an active low-viscosity lava flow develops a continuous and hard crust, which thickens and forms a roof above the still-flowing lava stream. (Photo by Margan Grover/UAA)

The Hawaiian uplands are treeless and sloping, like mountainsides. In a photograph, the landscape might look like tundra. "It kinda does, doesn't it?" Margan said. But it's not.

"This is a 3,000 year-old lava flow," she said, "and it's got grass and brush growing on it. It's a hard surface with a little bit of crumbly tephra," fragmented material left over from a volcanic eruption.

On the plus side? "No bears," Margan said. But watch out for field mice. At one camp site, "You unzip your tent to go into it, and they would just jump to get in," she said. At dinner, "You'd sit there eating and they'd scurry across your feet or up your legs."

What did they find?

As happened in the Aleutians, scientists first presumed humans spent nearly all their time along the coastline, where they had easier access to protein and food sources from the sea. Through Hanson's work on Adak, human use of the uplands became better understood. Work in Hawaii tells a similar story.

Evidence of a hearth or oven feature supports use of the lava tube openings by humans. (Photo courtesy Rachel McKenna/UAA)

The uplands here were considered only a place people might pass through on their way to another destination. A critical factor influencing this view was the lack of water. Now that perspective has changed.

"In the last few decades of research," Margan said, "one of the things they've figured out is that people would take gourd containers and find lava flows or rock overhangs where ground water would drip."

It might drip very slowly, but a gourd under the drip was a form of water storage, signaling long-term planning and use of the area beyond simple passage.

Their walking surveys found hearths at openings or collapsed sink holes in the lava flow. This might be a place with charcoal and gourd fragments used for cooking, dating to 250 years ago.

A pig skull is evidence of use by high-status individuals like chieftains. Pig was consumed at ceremonial events. (Photo courtesy Jay Rapoza/UAA)

Evidence of pig bones was an important find, Margan said. "One of the things we know is they only brought pig up when conducting ceremonies for chiefs. So the presence of pig is a sign that people of high status were working or doing things in this area."

Physical features in the landscape predate the arrival of humans. Depending on where you are [in the saddle between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea], there are 3,000-year-old lava flows and some that are 1,500 years old. People have only been in the area about 1,000 years, Margan said, and likely used the lava tubes for protection from wind, for food or water storage and even for personal safety.

The opportunity to create digital models of these upland sites is an exciting new development. "We're pioneering 3D modeling techniques that enable us to visualize what these sites looked like," she said.

This island saddle was a meeting place for territories managed by different chieftains, Margan explained, and trails follow boundaries between the distinct areas. An ancient traveler might have reason to seek shelter and hide.

"If a chief was coming through on his way to a ceremony," she said, "and needed to find someone for a human sacrifice, or for a slave, he'd take them captive, or take them to be sacrificed."

Stories of the chieftains and their ways came down through oral history, Margan said. Just as in Alaska, missionaries arrived in the 19th century to discover a very complex society with rich oral traditions. Newcomers wrote it all down, she said, "and then, of course, tried to stop it all."

Next stop, Oahu

Margan is finishing up the writing on a 130-page technical report on December's upland survey work. So far, all these field endeavors have been organized around academic breaks and holidays, which can put a time squeeze on faculty and students.

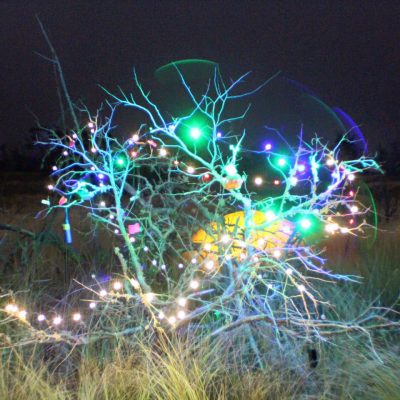

Near camp, the intrepid UAA archaeological team took note of the December holiday with brightly colored lights strung near their camp. (Photo courtesy of Gerad Smith/team member and UAF doctoral student)

"This past winter, we left the day after grades were submitted," Margan said. "I came back the day before classes started. So I was preparing final grades and submitting them, but also prepping my lecture notes and syllabus for classes I had to start as soon as I got back."

The start of fall semester will see a similar crush. Already Margan and a student crew-one UAA undergrad, three UAA graduate students, one UAF doctoral student and a professional archaeological field technician-are getting ready for their month-long stint in the jungles of Oahu in August.

The first day of class for fall 2016 is August 29. They'll be back, just in the nick of time.

Written by Kathleen McCoy for UAA Office of University Advancement

"Research in Hawaii: 'I've never crawled around in a lava tube before...'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Research in Hawaii: 'I've never crawled around in a lava tube before...'" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.