ADAC explores what 'opening the Arctic' really means

by Kathleen McCoy |

Extreme conditions in the Arctic make travel challenging. If a rescue becomes necessary, are we ready? (Image from Creative Commons: USGS, 2009)

Remember the Costa Concordia, the Italian cruise ship that capsized and sank after deviating from its course and hitting rocks off the coast of Tuscany back in 2012? Can you recall that image of the cruise ship, half-submerged on its side, laying still and empty in the warm Mediterranean Sea?

Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia capsized and sank after striking an underrated rock obstruction off Isola del Giglio Tuscany in January 2012. (Wikimedia. Used with permission by Creative Commons 2.0. Photo provided by By Lwp Kommunikáció.)

That ship had more than 4,000 people aboard. The accident occurred so close to shore that some passengers simply leapt into the water and swam for the beach. But not everybody could. Evacuation took six hours, according to reports, and 32 people died.

Flash forward to the summer of 2016, when Crystal Serenity, carrying 1,700 people, departs Seward on August 16 and heads through the

Crystal Serenity Northwest Passage route map, August-September 2016. (Image courtesy of Crystal Cruises)

Northwest Passage. Along the way, it will cruise through the North Pacific, the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas. It will pass Nome, Nunavat and Greenland. Plans call for a September 17 arrival in

Crystal Serenity, with 1,700 people on board, is the largest cruise ship to venture into the Arctic. It departs Seward on August 16. (Photo courtesy of Crystal Cruises.)

New York City. This is the first cruise ship this size to venture into the Arctic. If it goes aground off the coast of Barrow or somewhere in the shallow Beaufort Sea, swimming to shore in icy waters is not part of anyone's rescue scenario.

Mental images like this keep serious people awake at night. Even with Canadian and American rescue agencies fully engaged, how would communities like Nome, or Pt. Hope, or Barrow approach and accommodate a rescue operation like this? How might Arctic conditions like cold, ice and fog hamper a rescue? And cruise ship travelers are often older. How would they tolerate a slide down a 100-foot inflatable chute into a lifeboat pitching on the icy sea? Are lifeboats as designed today even adequate for an Arctic evacuation?

Good questions

Earlier this month, the University of Alaska Arctic Domain Awareness Center (ADAC) headquartered at UAA hosted the premier Arctic IoNS conference. IoNS stands for Incidents of National Significance. ADAC is one of 10 Department of Homeland Security Centers of Excellence. While the other centers focus on broad threats like terrorism, food or data security, ADAC is the only one with a geographic focus, the Arctic.

The lure of the Arctic includes polar bears. (Photo from Flickr by Maryanne Neslon,

Creative Commons license)

The pending opening of the Arctic-to commercial traffic like shipping barges and cruise ships, to science expeditions and adventurers-sparked this conference. The U.S. Coast Guard has broad responsibility for the sub-Arctic and Arctic off U.S. shores. With increasing travel and commercial pressure, ADAC serves the USCG, its principal client, by directing and providing research to fill knowledge gaps.

No doubt the pending departure of the Crystal Serenity helped focus minds around unknown or unrealized threats. Workshop participants represented almost 40 different entities, from the Canadian and U.S. Coast Guards, domestic and international weather services, cruise ship operators, communities along the route, hospitals, emergency managers and first responders, the Alaska National Guard and U.S. Army, even the FBI.

UAA was just one of the many universities represented, including UAF, Rutgers, Loyola, Texas A&M, Washington, Idaho and New Hampshire. IoNS charged the large study group to conduct "operator-driven research" that would address concerns in Arctic ocean travel. A second charge asked conferees to thoroughly examine "rescue and recovery of a fictitious disabled cruise ship in Arctic waters." In fact, the very situation at hand.

How the conference process played out

On their first day together, conferees listened to panel discussions covering a wide range of Arctic-related travel and potential rescue issues. On the first of five panels, operators like the Canadian and U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Army and Alaska National Guard laid out their major concerns should a cruise ship, or some other vessel, become disabled in Arctic waters.

Subsequent panels tackled challenges that are typical of any rescue operation-communications, medical emergencies, onshore hosting capacities-but discussed them in light of Arctic conditions or the physical capacities of those being rescued-say a large number of older cruise ship clientele-and how these issues could impact progress.

Lil Alessa, University of Idaho, led a break out group on rescue response coordination, situational awareness and communications. She and Dennis Egan of Rutgers University co-facilitated the group that included Canadian and U.S. Coast Guard, researchers, a cruise ship industry representative and others. (Photo by Kathleen McCoy / University of Alaska Anchorage)

On the second day, clusters of experts from government and academia gathered in four major breakout sessions to further detail concerns. Their work was called "a gap analysis," looking for holes in knowledge and reliability of necessary processes.

Example: the communications working group considered what in the Arctic might challenge effective communications. Would Arctic conditions and cold temperatures shut down communications technology that works fine off the coast of California or Maine? Since different countries are involved, can data from Canada or from the U.S. be used by anyone involved in the crisis?

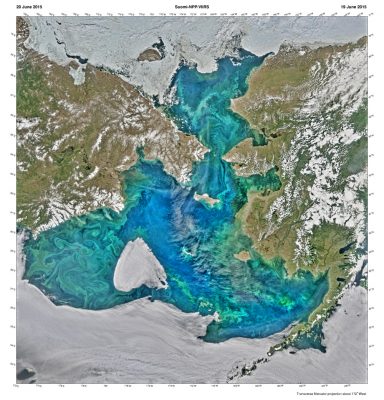

Satellite view of the Bering and Chukchi seas, courtesy of NASA.

They discussed the need to filter mass amounts of emergency data rapidly flowing from multiple sources down to information essential to a time-sensitive rescue. They called it the need for "thin pipes." When time is short, information overload can be a real threat to success. Lil Alessa of the University of Idaho, a co-facilitator with the communications group, also stressed the value of community- or place-based partners who may know geography and local conditions better than just-arriving first responders.

Other groups did similar work on the technology that exists to account for every person on board a cruise ship or in the rescue team, and whether Arctic conditions or an aging clientele might affect success. Another group dealt more specifically with medical rescue and technological challenges. In medical emergencies, the time it takes to get treatment is crucial. Would Nome be able to handle 1,700 evacuated cruisers, some in need of emergency treatment? Does the famous Gold Rush town have the capacity to support emergency personnel involved in a large rescue?

Another group considered how to achieve a 'shared situational awareness" at a distant and potentially dramatic rescue and/or recovery operation.

Putting needs into perspective

Douglas Causey, an ecology professor at UAA, serves as the principal investigator for ADAC. He explained the purpose of the conference this way: first responders like the Coast Guard already know how to handle rescues; they do it all the time. But what unique characteristics of the Arctic would challenge or hamper success?

While a malfunctioning crab boat in the Bering Sea is one adverse rescue scenario the Coast

The opening Arctic. This is an image of Burgermukta Glacier near Svalbard. (Taken by Gary Bembridge of London UK https://www.flickr.com/people/8327374@N02)

Guard knows, safely evacuating almost 2,000 people from a cruise ship in Arctic waters is quite another. If an incident happened off Pt. Hope, could a rural community accommodate rescue workers and survivors? What if an evacuation happened in the Beaufort Sea, with no existing ports and communities? Together, teams with experience in logistics, first response, medical and technical expertise, worked to surface critical unknowns so that research could be directed to fill the gaps.

This way, Causey explained, "the unknowable can be approached. What are the issues that keep us up at night? Second, what existing research can fill those gaps, and what new work needs to be done."

Before the second day concluded, each break-out group had chosen at least five subject-area questions that needed more work or answers. Their reports went to Causey, who will prioritize concerns and forward them to the Department of Homeland Security. With agency approval and funding, ADAC will advertise in academic publishing channels for researchers to tackle the work.

"Ultimately, this is less about rescue, and much more about clearing up knowledge gaps," Causey said.

Sunsets tease the Arctic horizon as scientists on board the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy head south in the Chukchi Sea. (NASA image)

Written by Kathleen McCoy, UAA Office of University Advancement

"ADAC explores what 'opening the Arctic' really means" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"ADAC explores what 'opening the Arctic' really means" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.